IT seems a long time since anything about the Church's Missions in this interesting island appeared in the pages of Mission Life. Since the last note, however, appeared, the Missions of the S.P.G. have been conducted as usual, and we have to record that, notwithstanding the many opposing influences brought to bear against the work in Madagascar, such as political influence, immorality, unhealthy climate, indifference, sloth, and deep-rooted prejudice in the minds of some, God has been mercifully pleased to bless our work even beyond the most sanguine expectations. Kind friends at home have nobly helped and encouraged us. Many prayers offered by those we have never seen have been heard, and have brought down a blessing on the teachers and the taught. Still, though it is so, be it not for a moment suspected that in other respects we are more favoured than other Missions. Death has carried off our chief pastor, who, though holding the see of Mauritius, became known to our people and beloved by his care for them during the short time he was permitted to be their bishop, and before, when diocesan secretary. When the sad news reached us here, it was distressing to see the grief of the poor ones of Christ's flock as they came in mourning, and, after their national custom, sat down to weep. Death, too, has visited the flock, and some, both children and adults, whom I was privileged to baptize, I have been called upon to bury. So uncertain is life. As regards the living, some give us great comfort and some give us great anxiety.

Humanly speaking, we should have been far more blessed had the labourers in this part of the vineyard been more numerous. Ever since the Mission has been first established it has been sadly undermanned. One Missionary has been left alone since September, 1869.* [Footnote: * We may add that two Missionaries have lately been appointed to Tamatave, the centre of the S.P.G. Mission in Madagascar.] We are, however, gradually going on. I am by no means prepared to claim for the Church's Missions what is claimed for Missions in the interior of the island. A great work is before us. Congregations everywhere assemble, whether there are teachers or not. In many places the inhabitants of whole villages still assemble, because it is the will of the Queen. They gather themselves together, they sit and talk, waiting for a teacher and preacher to come: and none comes. They reduce their meeting almost to the level of one for transacting worldly business. Even when there is a native preacher, not under the direction of a Missionary, the Sunday gathering does not seem to attach the importance [283/284] to praise and prayer. In many places they assemble to do they know not what. In some cases the praying and preaching is conducted by a mere boy, who can scarcely puzzle out a line in the New Testament. The land is still thirsty and barren. Oh! that God would put it into the hearts of some to come and join in sowing the seed over this wide field of ignorance and sloth. Thousands upon thousands assemble, but they are not yet brought to the foot of the Cross. The name of Jesus many may know; but Him they know not.

Still among the many who are called I would humbly believe that there are and will be some chosen: humble, faithful, loving souls, bearing the stamp of their Saviour, which He knows now, and will recognize in "that day." What I would have English people guard against is the impression that nothing remains to be done in Madagascar. Without at all disparaging any society, or attempting to detract from the great and noble work which each on its own plan has performed, it is clear that the mass of people in Madagascar is still without the leaven of Christianity, and that holiness, purity, and truth are unknown to by far the greater part of them except by name, and as something which they are not expected to offer as a sacrifice to God.

In the more distant parts of the kingdom reports constantly reach us of the great things done in the capital, but the only effect these reports seem to have on the officers stationed at the different outposts, is to make them throw as many obstacles as possible in the way of Church Missionaries. So far, however, as the Church's work is concerned, we have, so far as we could, thankfully embraced the opportunity which as opened out to us new spheres of labour.

Seven years ago there was no Malagasy in Madagascar in connection with the Church of England. Now our farthest station is about 400 miles to the north of the chief town, Tamatave, on the coast, and is occupied by the C.M.S. The work of the S.P.G. lies between the two, with its chief Mission at Tamatave. A person, therefore, visiting Madagascar would now find the Church on the coast, with its twenty or more congregations. Let him go into one of the churches, and there he will find people who, seven years ago (for the two Missions of the Church were simultaneously planted), knew nothing of God or of His Word, now joining heartily in the Church Service, reading as well as many a one in England, following the preacher with earnestness and attention, zealously hunting out in the Bible the references he makes, and occasionally jotting down any new thought suggested to them for pondering over at home. And if he stays to celebrate the highest act of the Church's worship, he will find a goodly number approach the holy table with such reverence as makes apparent their appreciation of the precious gift they are receiving.

Such a one's heart would have warmed could he have seen a little [284/285] festival for the children, held at the beginning of October last, at the central part of the S.P.G. Mission. It was simply the annual treat. The early part of the day was close and lowering; now and then the spring sun struggled through the clouds and lit up the festive scene with gladness, revealing many clean and bright-coloured "lambas" and happy faces. At 8 A.M. the children assembled in church for service; and the zest with which they sang their favourite hymns seemed to show how they were longing for, and pleased with the prospect of, what was to follow. The Archdeacon of "Seychelles" (Diocesan Sec. of C.M.S.), then staying at Tamatave, gave an address, which I translated into Malagasy. Service over, the little ones left two-and-two, and were joined outside by their banners. They then marched through the town. Here a storm of rain greeted them unpleasantly. But no sooner was it over than the sun shone out gloriously, and a beautiful day followed. On they went, like some band of small soldiers, their banners fluttering in the breeze, and making a very pretty sight, as they wound their way by the sea-shore to the place where they were to enjoy themselves under the trees some distance in the country. Here they were met by two schools from our two out-stations to the S., and all together numbered a happy group of 125 children. Many from the congregation accompanied them, and others came from the southern villages. Some Europeans, too, residing at Tamatave, and having an interest in our work, we were glad to welcome among us. Then the fun for them and work for us began in earnest.

We went out "a-picking sticks," and soon fires were blazing under the trees; and warm work it was, with the fires round us and the grilling sun above us. A bullock which had gone before us in the morning had, in the meantime, been killed. This was now boiled in immense pots; as were also two sacks of rice, which we had brought with us. The children were arranged under the trees, and sat on the ground. The broad leaves of the banana trees served as a cloth; and the same, done up in a way peculiar, I think, to the Malagasy, were used as spoons. Meanwhile the Hova band arrived from Tamatave, and enlivened us with music, though of no very grand or elaborate description. The meal over, they regaled themselves with what the Malagasy are so passionately fond of--bananas and sugar-cane.

Next came the sports. A few days previously I had received a box of clothing from a kind lady at Canterbury. This came in splendidly for clothing. They raced, jumped, played at different games; and late in the afternoon, headed by the band and eighteen palanquins, they returned home. It was a most joyous day; the children evidently enjoyed it thoroughly; and, on the whole, it appears to have been well calculated to incite them to make progress in their studies. A little number has been gathered into our schools; but when we remember that it is possible to get four or five times that number with an efficient staff of teachers, it [285/286] will be seen that much remains to be done; and that much can be done, if only our wants are supplied. A schoolmaster is wanted sadly, and has been asked for; but I suppose the Society cannot afford to send us out one.

NOT long after the chief Mission of the Church had been founded in this island, they began to extend to the neighbouring towns and villages. Through the exertions of the Rev. W. Hey, an old Augustinian, whose death we have since had to lament, a small Mission church was put up at a village about twelve miles to the south of Tamatave, named Toondrona, and a congregation gathered together.

In no place in the island has the work been of so discouraging a character, Toondrona being only too well known for its rum-drinkers. Never as day can you pass between it and Tamatave without overtaking barrels of rum being rolled over the level coast for consumption at Toondrona, and meeting as many empty ones being rolled back to Tamatave for more.

The people there are in consequence fearfully degraded: ignorance, vice, and misery reign supreme, whilst the indifference to religion almost amounts to a determination to have nothing to do with it.

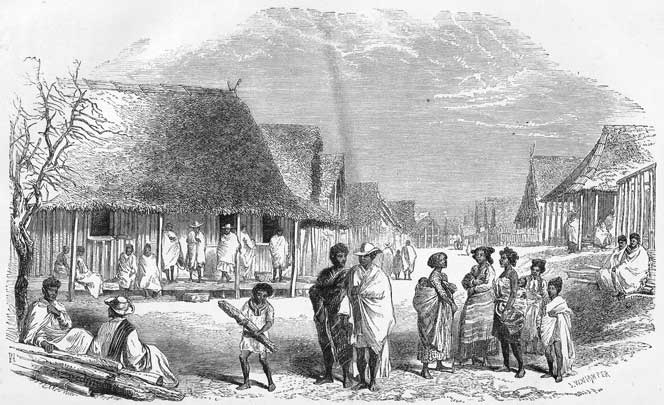

Pass though the town at whatever time you like, and whether it be "morning, noon, or night," you will be sure to hear the clap-clap and the miserable drawling songs of the revelers; not a very enticing place certainly for work, but just the place which the Church delights to enter, to conquer, and save. I must not forget to say, too, that most of the inhabitants are "inpandalo," people whose business leads them for a time to the coast towns, so that after rioting for a few days at Toondrona they are gone and not seen again for long.

Still, even in this uninviting place the Word of God has been plainly declared. A good number there can now read fluently; one man occasionally acts as catechist, and a nice little school is being gathered together. One grieves that the single Missionary attached to the S.P.G. Mission is not able more frequently to pay visits to and pass more time at this place.

I was lately called upon to bury one of our firmest adherents at Toondrona, a man of whom, though poor, it may be said that he was foremost in every good work. John Lehifotsy was a Hova, and got his livelihood by trading in rice. After a long season of preparation I baptized him. When he came for holy baptism he could read very nicely, having almost taught himself. As a memento of his baptism, if he needed one, I gave him a Prayer-Book; afterwards, when visiting the church there, I was almost sure to find him sitting at the church-door diligently reading it. [323/324] For some time his health had been gradually failing. Consumption at last carried him home very rapidly,--so rapidly, in fact, that it was impossible for me to go and see him, much as I wished it. But I feel sure that as his love and devotion were great, and his faith in the One Precious Sacrifice greater, he may now be numbered among the blessed. On my arrival, when I went to bury him, the greater part of the congregation came to me and mourned the loss of their brother, calling him the pillar of the Church there, as indeed he was. The church was quietly prepared for the funeral. The body was laid on two stools, placed as the dead are at home; the women with disheveled hair, the sign of mourning, sat weeping to my right, and the rest of the church was crowded, many of the people being heathens. I could not help giving them a short address.

Toondrona was originally one of the out-stations of Tamatave. Since, however, the new and larger station at Mahasoa has been opened, it belongs to that district.

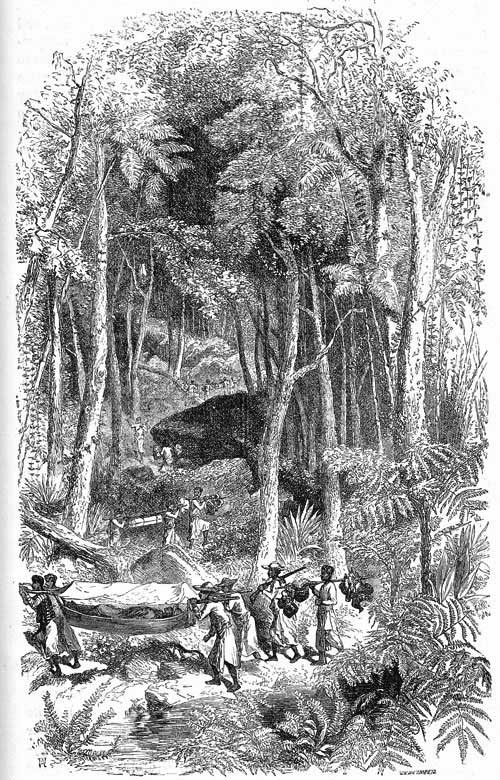

About nine months after the arrival of the first Church Missionaries at Tamatave, the Rev. J. Holding formed another out-station at a northern port, named Foule Point. Of late we have been compelled to leave this place to a catechist. However, I managed in October to pay it a visit. The distance from Tamatave by land is about forty-five miles, by sea about twelve leagues. One can scarcely put out to sea in a Malagasy piroque, neither could you make up your mind to wade through fens and marshes, unless you wished to die of the fever forthwith. Neither would one care to sleep in the midst of the said fens and marshes. Consequently I was obliged to resort to the ordinary mode of traveling here, in a chair, palanquin fashion. Forty-five miles in an express train is only a matter of an hour. In a chair carried by eight men it is a tremendous day's journey. I left Tamatave in the early morning, and arrived at Foule Point about six p.m. The country between the two towns, notwithstanding its extreme unhealthiness, is sometimes, but not uniformly, very pretty. To the eastward you had the calm sea flashing back the sun's light through masses of foliage on the shore; to the westward, nearly hidden by trees of various and wondrous kinds, the small lakes were calmly sleeping, their stillness scarcely broken by some solitary canoe skimming over their surface.

I should certainly like any at home who wonder how it is we manage to catch Malagasy fever, to see some of the parts we had to travel through. One could in many places almost taste the miasma, horrid, fetid standing water, of a dark brown colour, but often quite clear. This our men had to go right through--no avoiding it--and the filth from below came boiling up. Out of that over the marshes you went--into them, I should rather say--the spongy soil squishing under every step, and the sun burning over head. In the several bad localities the malaria must be something very deadly. And if be true, as some say, that [324/325] malaria never crosses a river, nature has not provided such a defence against it for those who live at Tamatave and Foule Point. The Malagasy seems to have played a cruel joke in giving to Foule Point, the native name of "Mahavelona," which means "making to live," for no one who has seen it can consider the climate there as anything but "Mahafaty," "making to die."

On my arrival I found my way at once to the church, which is nicely situated, and large enough for our present wants. I then sent for the catechist, and we had a good long examination into the several matters I had come to arrange. One very delicate question--whether one of the Christians would receive back his wife, whom he had put away without cause--is not yet finally settled. Other matters were connected with the good of the Church at large. The Church had sent out teachers on Sundays to villages north, south, and west. On my way up I stayed a short time at one of these villages, and inquired as to the prosperity of the Church there. I was met by the discouraging answer, for which, through the catechist's letters, I was prepared, "In former times a teacher came from Mahavelona every Sunday to teach us and we assembled, but now he comes no longer."

In 1869, at a dangerous season of the year, I went to the capital with the Rev. H. Maundrell, of the C.M.S. Mission, to endeavour to secure for our people at the distant stations from the Malagasy Government that religious liberty which had theoretically been secured to them by the British treaty. Our mission was most successful, as seen by the letters subsequently sent to the several Hova governors in the districts of our respective Missions. But semi-civilised nations require the continual reminder that treaties are made to be observed, and that the effect given to their terms by their own governments is to last as long as the treaties themselves. One great object I had, therefore, in going to Foule Point was to see that the members of the church there, and those in the neighbourhood wishing to put themselves under our rule, shared the practical benefit of the treaty, which, at such a price of bodily suffering to ourselves, we had previously secured for them. I found that the congregations to the west, north, and south, in all four, had been deprived, by apparently some unjust measure, of the services of the teachers who every Sunday had been sent out the by the central Church to preach to and instruct them. In no one instance have we ever attempted to stand between the law of the land or the Queen's message to the people (as binding on them as law) and the subjects of the Malagasy Government, nor have we attempted by any kind of interference to weaken its political and moral influence on the people. Our aim, when we could do so without compromising ourselves in any way, has rather been to give effect to its directions; and most unflinchingly have we done so in regard to matters of religious freedom. For, if we get converts, we can in many cases only hold them [325/326] by demanding in the firmest terms that they may be allowed to use the liberty granted them by their chiefs. Hence it cannot be said that we have meddled in matters which don't concern us, in demanding that at least their Sundays may be spent as they like. Other days we know that they have their several duties to perform for the Malagasy Government. Their time, their all, is then at it is disposal. But the Sunday has been given as a day of rest, and as a day when no "Fanompoana" (Government service) is required of them. In fact, so strict has the Sunday become on the coast, that many look upon going to chapel (where they are sometimes driven by the soldiers) as another and equally hard form of labour they are bound to perform. It may therefore be said that, inasmuch as the Queen has given the Sunday (I say the Queen, for if a Queen hostile to Christianity were to ascend the throne, she would, according to Malagasy ideas, have the right to turn the Sunday into an ordinary day) as a special day of rest and prayer, the governors under her have no kind of right to abrogate her decree.

The morning following my arrival at Foule Point I conducted service in the church, having previously called and examined those who, of their own free-will and at their own expense, had gone out on the Sundays as teachers and preachers. On such an occasion I deemed it best to give an address rather than a sermon. They followed with close attention, as I gave a review of the history of the Mission from the first, and showed them how at last, when all seemed to be flourishing, when four congregations had been gathered in the neighbourhood, and Sunday-schools had been established, then the Governor of Foule Point, for some unknown reason, gave orders to our teachers, and apparently to them only, that they could no longer absent themselves from Foule Point on Sundays, as they were wanted for "Fanompoana." For the comfort of the people I rehearsed to them the reason and the result of my former visit to the capital, and afterwards found it gave them great confidence.

In the afternoon I had a class of catechumens who were that day to be baptized; six of them being lads from twelve to fifteen years of age, the rest adults. I was astonished by their replies to my questions. The Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments they said perfectly, and answered well my questions on points of doctrine.

The Church at Foule Point is by no means a handsome one. It is a purely Malagasy building--rush walls, leaf roof, and bark floor, the inside being lined with mats. Assembled again at 4 p.m., the people sang very heartily the hymn before the service. After the second lesson followed the baptisms. No sooner had we finished the hymn before the sermon and the text was given out than in the distance we heard the faint music of a native hymn, gradually and slowly getting louder and louder. At last it came very near, and, looking through one of the windows, I saw a body of people marching four deep, and headed by the Governor, approaching [326/328] the church. They were the native Hova congregation come to show that they were one with us! Such an event was of the rarest occurrence, and is to be explained only by the supposition that some one who was present at the morning service had conveyed to the Governor the substance of my address, which produced in him a healthy fear. They all came pouring in, one after the other, and when all were seated I continued my sermon, and again alluded to the freedom of worship enjoined by the Queen and Government. After service I had a long talk with the Governor, in the course of which he asked me to come and preach to them when I next visited Foule Point!

I left Foule Point again shortly after 3 a.m., and, after a long and hot day's traveling, reached Tamatave in the evening.

With regard to our work at Tamatave, the readers of Mission Life will rejoice to hear that we have lately received a most handsome present from kind friends in England, in the shape of a carved stone font, inscribed with the words, in Malagasy, "One Lord, one Faith, one Baptism." Before it was put up it was lying for a few days in our temporary printing house, and then one of the Malagasy, well acquainted with the great differences between our Church's mode of worship and those of the other forms of Christianity in the island, said that "the English Church reverences what pertains to public worship." It is to be hoped that the due reverence paid to holy places and things will in the long run work its effect on the minds of the Malagasy, who are now disposed to look down upon anything not peculiarly Malagasy. When the font was put up, at its inauguration thirty little ones from our schools were baptized in it--a glorious increase to the little band whom we hope to see faithful soldiers and servants of their crucified Lord. It was a most cheering sight to see them gathered round the font--most cheering to see and feel that, in spite of illness, want of labourers, and perhaps worse than all, a steady, determined chronic opposition, we are making an impression for good on the hard and stubborn heathenism, indifference, and depravity of this eastern coast of Madagascar.