|

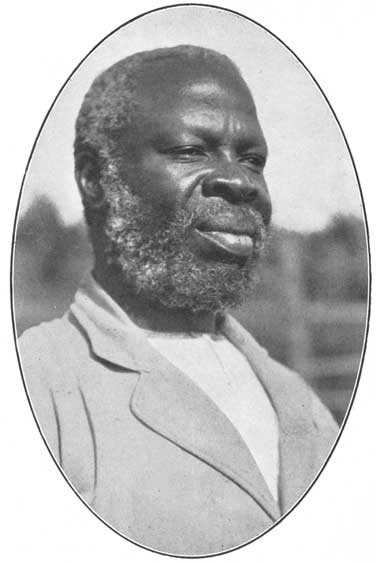

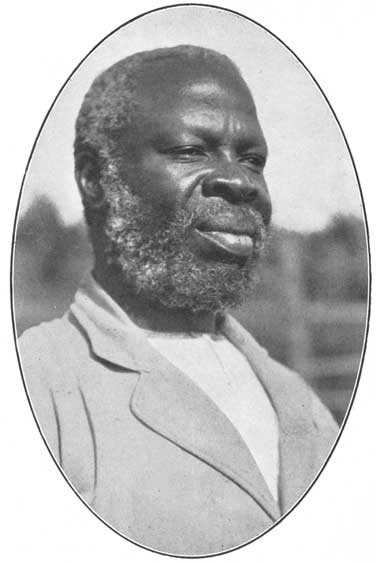

Rev. Preb. W. Wilson Cash, D.D. LONDON AND EDINBURGH |

|

Rev. Preb. W. Wilson Cash, D.D. LONDON AND EDINBURGH |

WHEN Mackay, a young engineer, began his work in Uganda, he saw the African in the raw. A cruel king burnt the first converts to death, tribe made war on tribe, fear stalked through the land by day and terror by night. Missionary faith and vision saw the native not as he was in his cruelty, superstition and lust, but as he would be through the redeeming love and power of Christ. Faith became fact as young Baganda men accepted Christ as their Saviour and Lord, and the vision was realised as the slaves of the African forests entered into the liberty of the sons of God. Few people in the days when Caesar conquered Britain could have seen, in the savages of these islands, such Christian leaders as Wesley, Carey, Henry Martyn, or Duff. In much the same way in the early part of the nineteenth century people only saw in the African a man with a slave market value. Yet the same Gospel that redeemed us, and turned a wild pagan race in Britain into the evangelists of the world, is now operating in Africa, and the black races of a dark continent are reaching out in evangelisation to the legions beyond.

Nowhere is this better illustrated than is the life of Apolo, the Apostle to the Pygmies. His story is one of heroism and faithful service, of devotion and obedience to the Call of God, of suffering and hardships gladly borne for the sake of Christ. This greathearted African was called to his rest last year after having seen scores of Christian communities spring up, and the foundations laid of the Church of God in the forests of the Belgian Congo.

Mr. Roome has had unique opportunities of studying this great work in Central Africa and he speaks therefore as an eye-witness with a first-hand experience. He writes so vividly of what he has seen that the story of an African hero comes to life under his pen, and we are carried in vision to the heart of Africa to share with our brethren there the glory and the splendour of the triumphs of the Cross.

After reading this book my feeling was one of deep thanksgiving for this fresh evidence of the power of Christ in human life. "Ethiopia shall stretch out her hands to God." Surely this prophecy is fulfilled as we see men like Apolo giving their lives in a full and glad consecration to the service of their Master. This book is a challenge to us all to stretch out our hands in the offering of our lives and our all to Christ, who has redeemed us unto God by His blood.

W. WILSON CASH.

THE writer of this story greatly treasures the memory of his friendship with Apolo and their travels together in search of the Pygmies. He also acknowledges his debt to Herr Paul Schebesta who lived for a long time with these little people, and to the story, Among Congo Pygmies, from which he learnt so much.

WHAT would you think of a forest as big as England, Scotland and Wales, and one able to tuck in Ireland alongside? That gives you some idea of what a teal African forest can be. No wonder in such a forest there are all sorts of wild beasts, and perhaps even wilder folk. The trees are so tall, and often so clothed with leaves, that no sunrays can get through them. There are only a few main roads through these forests. Nearly everywhere you go you just have to walk, walk, walk along the tiny tracks. These tracks have often been made by animals first, then the black folk have come along and used them. As these people always walk in single file, the pathway seldom becomes wider than a foot; marching along it necessitates care. You can quite understand what a very narrow track that would be, with dense bushes and young trees, on either side, growing up between the trunks of the great trees. Sometimes these lower bushes are so dense they join their branches overhead. You will find yourself really walking through a green tunnel. Try and imagine how dark and gloomy such a forest would be. If it has been raining the night before, it will be drip, drip, drip all the day long, from the great trees overhead. What a wildly weird, romantic country it is!

This forest is in a land of tropical sunshine, where, except for the stormy wet season, the sun generally shines all day long. It is hot indeed!

Elves and fairies, have you ever seen them? I wonder whether you really believe in them? You will most likely have read many stories of fairy folk, and these books may have had wonderful pictures of little folk playing in the forest around the toadstools. I am afraid most of these stories that you will have read are just "fairy stories"! Well, if you like to believe them, you can. I am just going to tell you a real live and true story. If you will come with me, I will take you in imagination to this Fairy Land. Here we will find the real little pygmy folk playing in the shade of the great primeval forest--in Congoland--away on the continent of Africa. Perhaps you will remember this has often been described as the Dark Continent. Well, here we really have dark country, and dark people.

I have been through this great forest several times and it has meant a long, long march of hundreds of miles each time. All day long, shut in by the great trees and the bushes I have described, perhaps for weeks never seeing more than a few hundred yards ahead.

In the middle of the day we would stop for a little rest and refreshment. We may not have seen any folks all through the morning march, then, as we may be resting, voices may be heard. People have found that someone is travelling through their forest, and they are quizzing round to find out who it is; or there may be a little family of travellers--with them a goat, or a monkey. At night-time we just find a more open spot, unless fortunate enough to find a convenient village, and there camp, in a little tent, if you've got one, or perhaps in the open. If it is a wet night, you may be very glad to creep into a native hut.

After a few hours' march, you may see a blazing light ahead. Here is a little village, where some of the tribes of the forest are living. The sun is so dazzling, in this open place, that you are glad to pass to the other side of the village and enter another "tunnel." In these villages are all sorts of wild folk, especially in those places where no Christian Missionary has ever been to tell them of the love of Jesus Christ. As you live in a Christian land, with all the comforts and protection that that means, you just will not be able to understand how dark a heathen African village is, where the Light of the Gospel has never been taken. And oh, what sickness and suffering there is where no kind Christian Medical Missionary has been to bring them healing and health. Even in small communities of people, there will generally be a witch-doctor who terrorises the people, while pretending to heal them. Also in these forests, in some of the darkest far-away spots, there may still be cannibals, people who eat each other.

One day, after I had been camping in such a village for the night, I started my march as soon as the sun got up. A few miles along this forest track, while it was still quite gloomy, a little man rushed past me. Such a little chap he was. What a scared look he had! I believe he had never seen a white man, as I was told no white man had ever been into that part before. I knew at once that he was a pygmy, a little forest dwarf, and that he would not be living alone, even though he had been starting that morning on a lonesome hunt.

As I was very anxious to see some of his friends, I asked my guide, a black man who lived in those parts, if he thought he could find the pygmy colony. We went on for a few miles more, when suddenly my guide stopped. He pointed to a hole in the bush at the right. It was so low, and narrow, that you would not think anything bigger than a goat could go along it. My guide went down on his hands and knees, and began to crawl through. Of course I had to follow in the same way. We went like this for what seemed a very long time. At last we were able to stand up, but we still had to fight our way through the bushes. We came to a rocky river, with swift-flowing water tumbling over the rocks. It looked as if it was the end of the path. There was nothing on the other side of the river, that we could see, where we would be able to continue our march. The guide indicated that we had better walk up the middle of the river. We did so, splashing through the water, and tumbling over the rocks for what seemed some half a mile. Then my guide stopped suddenly, and pointed to a little track on the right bank. There was a muddy patch. We could see some very small footprints. My guide looked all round to see if he could find anybody. We could not see, or hear, any one, so he said it would be well for the white man to wait there while he went on to find the pygmy encampment, and make friends with them. It would not do for a white man to arrive suddenly, and startle them! Without meaning to be unkind they might shoot some of their poisoned arrows at the stranger, just to make sure whether he was a friend, or foe. After a time my guide came back to say he had found them.

We started off along the track, keeping a close look-out among the trees. Some distance on I could hear rustling, and all at once I saw some of these little folk, half hiding behind the trees, and staring at the stranger. What a scared look most of them had! They kept their bows and arrows ready in their hands.

At last I reached the first of them and tried to be very friendly with him, but, of course, I could not speak to him, not knowing his language.

That first view of these little folk was just like a picture out of a fairy-story book. They were very substantial fairies though! Little wild folk about four feet high, some of them not so tall. Very sturdy bodies they had, for they are great hunters; and very strong, although so small. They were not very beautiful to look at, as we understand beauty. Their faces are far too much like those of a monkey, and their bodies are very hairy.

When these little folk had got over their shyness, we all went along the track together, and we found the encampment. By that time there was quite a crowd of them. They do not build proper villages because they do not stop long in one place. They are always hunting through the forest. When they want to stay in one place for a few days, or a week or two, they tear down some of the undergrowth, and build their tiny huts under the shade of the big trees. These huts are made of small branches stuck into the ground, and covered with leaves. Only a very small boy, or girl, could stand up in one of these huts.

After they had recovered from the startling arrival of the white man, they became quite friendly. I told my black boys to get out my breakfast. This gave confidence. Soon a whole crowd came gazing round, chattering away to each other. If one could only have understood, how interesting it would have been to know what they were saying, what they were thinking about this white stranger in their midst. After the excitement of breakfast, they started one of their weird dances. What a merry little crowd they looked! What shouts they made! Some of them started making a great noise by beating their hands on their bare chests, just the sort of "plop" that you would hear if you blew a paper bag full of air, and then burst it. This is the way they find out each other when hunting in the dark forest; gorillas also do the same.

After breakfast, I thought I would see how they could shoot with their bows and arrows. We fixed a little scrap of paper on a tree a long way off. They shot at this mark. Their aim was so good that, if it had been a pigeon instead of a scrap of paper, most of their arrows would have hit it.

Then I tried them at climbing. The trees in that forest are generally straight for fifty feet or more, before the first branches grow out, that is because they are so close together. If you can imagine the biggest telegraph pole you ever saw, it would give you some idea how the small trees look. I wondered how they were going to climb it, as there were not any branches to get hold of, and the tree was far too big for them to put their arms and knees around, as we should climb. That did not trouble them. They climbed up with their hands and their feet, just very much as pussy would do, and were very soon up at the first branches. When they got there, they just stood up, and ran along the branch. They soon had their bows and arrows ready for any animal or bird they might see. When they were climbing the trees, they carried their bows in their teeth.

All through this forest there were many animals, big and small, beside the elephant and the buffalo. Wild pigs, troops of monkeys of every kind, including the chimpanzee. Leopards, wild cats and snakes have their homes there. In the forest overhead there are many birds, including parrots. The ground is crawling with insect life. This often makes it uncomfortable, and difficult, to sit or lie down.

The shades of night gently spread over the dreaming forest. Darkness stretches its veil across the little camp. Dance and song come to an end. Bathed in sweat, the pygmies crouch over their fires, or lie on their leafy beds, and chat in subdued and drowsy voices, which, after a little while, die away altogether. I stretch my weary limbs in my camp-bed and fill my lungs with the cool night air.

Absolute silence reigns. In moments like these, thoughts stray back to home and family. Detached from their immediate environment, they travel in one precipitous leap over thousands of miles of virgin forest, sea and mountains to another land, where spring is just awakening. Here nature is overwhelming and terrifying in her wildness and primitive brutality. At home God makes His presence felt in the soft whispering of the wind, and in the beauty of the flowers. Here He speaks in thunder, and the roar of the storm, amongst gnarled, sinister trees of the woods. There is an eerie stillness about these nights in the tropical forest. Black magic seems to call when the wail of an owl thrids the air. The pygmies, huddled together in their huts, terror-stricken, say it is the Voice of God. A distant growl smites one's ears, and makes the black uncanny night still more unearthly.

HOW often have these questions been asked. What do we know about their history--if any? Yes, we do know something, both in story and in picture. On some of the temples in Egypt, built by the great Pharaohs thousands of years ago, we find pictures of these quaint little folk. There is no mistaking their likeness. One of these great Pharaohs was called Nefrikare. As far as we know at present this Pharaoh was one of the first to tell us about these, as some people imagined, legendary little folk. There is a letter to his Commander in Chief called Herihuf, which gives us the following story:

"I have noted the contents of your letter to me, your King. I learn from it that you have penetrated with your troops into the land of Iman.

"In your letter you also state that you are preparing to bring with you many choice gifts, which Hator, the goddess of Iman, has prepared for the person of Nefrikare.

"I further learn from your letter that you are bringing a pygmy with you, who dances the dance of the gods in the land of legend, a dwarf apparently like the one whom the treasure-keeper of the gods, Baured, brought from Punt in the days of Aosis. You also inform my majesty that never was anything to equal him in value brought home before by any servant of my majesty.

"You have the pygmy in your retinue whom you have brought from the land of legend, so that he may dance the dance of the gods, and thereby fill the heart of King Nefrikare with joy.

"When you bring him to the ship, choose reliable men to keep watch on both sides of the vessel, kst perchance he may fall into the water, and when he sleeps at night tell off ten stout fellows to sleep alongside him.

"My majesty yearns mightily to see this pygmy.

"See that you bring the pygmy alive, hale and sound to my palace, and then my majesty will confer on you far higher awards than those given by the treasurer of the gods in the days of Aosis. From this gauge how great is the yearning of my majesty to see this pygmy."

Has the pygmy always been a dwarf? That is a question we have no time to discuss here. Probably, thousands of years ago he was just the same size as an ordinary negro, living in the open country, then driven into these dark forests, living in constant gloom he has degenerated till he has become what he is to-day, about the lowest in the scale of the human race.

As we find them to-day the pygmies ate very companionable little folk, always willing to share with their comrades the results of the hunt. They even care for their sick folk and old people. Somebody always looks after them, and provides them with food. The pygmy is not always particular, according to our ideas, of the sort of food that he finds useful. Amongst the many articles of diet, they are very fond of caterpillars. There is a particular sort that thrives in the forest. Sometimes these caterpillars swarm enough to cover the trunk of a tree. The pygmies then indulge in a most enjoyable feast. They do not wait to cook the grubs, but just let them crawl down their throats alive, and, if they are too slow in their crawl, just hurry them down with a bite!

It is said that the pygmies do not know how to make fire, although tribes around them do this with the sparks from flint, or the whirling of two sticks.

Although the pygmies are continually ranging through the forest, they have clearly defined home territories in which each group hunts. Each also has their own special anthill or hills. They are particularly fond of this delicacy.

Everything in their territory is common property. It seems strange that the pygmies, who have lived so long in association with the more advanced negro, have not sought to imitate them in the improved standards of living. Apparently their wild life has become so natural to them, that they see no attraction in the higher development of the tribes around them.

THE pygmies are great elephant hunters. While the ordinary negro attacks the elephant from a distance with his throwing spear or arrow, the pygmy stalks him to close quarters. Every hunter has his own spear, which he treasures with the greatest care. On the eve of an elephant hunt all the women in the camp hold a magic dance, in the course of which they squirt water from their mouths with a view to bringing luck to the hunters. At early dawn the hunters have a silent, hurried meal, and start off in batches of two or three. Cautiously and silently they creep through the forest till they find some huge beast. When once found it is doomed!" In their hunting pygmies sometimes use the poisoned arrow. The poison is not made by each individual, but by special men. It is extracted from the liana leaves and stem. While one man sees to the pounding, another makes a press of rattan reeds, one end of which he makes fast to a small tree. A stick is inserted at the other end, which is twisted rapidly round until it squeezes out the soft succulent mass so thoroughly that its juice drops into a vessel placed beneath it. The hunters with their arrows are quickly on the spot, and light a fire. The arrow points are dipped in the poisonous extract, and held over the fire until the sticky stuff adheres to the wood. Then they place the arrows in the sunshine until the poison has thoroughly dried. Before the arrows are collected, their poisoned tips are carefully wrapped in leaves and bast, to minimise the risk of accidental wounds from them. The process of preparing poisOn is not of frequent occurrence, and the hunters always equip themselves on these occasions with sufficient arrows to last them for some time to come.

Silently they dodge the giant among the trees, then one of them steals up as close as he can and aims at the knee joint of one of its back legs. In a flash he is back in the shelter of the undergrowth. The elephant, maddened with pain, turns on his pursuer. A second pygmy attacks the other back leg. Thus the animal is rendered helpless.

Then the pygmies creep up cautiously and hack at the trunk, causing it to bleed to death. The tidings are sent through the forest. Soon the crowd gathers, and die feast begins.

Herr Schebesta says:

"When an animal has been killed in the chase, the eldest of the tribe cuts it up, and distributes it. The heart and liver go to the man who has shot the game. A fragment is cut from the heart, and thrown into the forest. Later I learnt the meaning of this strange custom, for the incident that I had just witnessed stirred my curiosity. When I made closer inquiries into the religious rites of the pygmies, I found that they always sacrificed the first-fruits of their labour to their gods.

"The pygmies are very fond of hunting toads for food. When these creatures are particularly noisy in some pool at night, the pygmies will make a raid on them. One of their favourite delicacies is honey. This they find wild in many an old tree-trunk. A man forces his way through bushes and brambles to the trunk, which he smites with his axe, while he intones:

"'Aja, wa, wa, wa, wa, wa, papa mekwiti!'

"Translated, his invocation runs thus: 'Father, permit me to find honey!' A prayer to the deity for abundance of honey,"

BUT we must get on with our story of Apolo, the Apostle of Pygmyland. He is an African clergyman of the Christian Church in Uganda. He has been the messenger of Good News to these little pygmy folk. What a wonderful message he has taken to them!

As these pygmies have lived hidden in the dark parts of the forest, it has been very difficult for white men to find them. This African Missionary, knowing the ways of the forest and the people there, has found them and he has become their great friend. He has so won the confidence of these, the shyest members of the human race, that for the first time in their history, they have learnt something of the great world beyond their forest, and the coming of men of another race who care for them, and want to bring them good news.

We must go back in our story many years to learn something of Apolo's life. He was born about 1864. The country of Uganda, in Central Africa, was first discovered by Stanley, the great explorer, in 1875. He sent home to England the first news of this kingdom and its people. It was in response to this story that the first Missionaries of the Church Missionary Society went out two years later to commence the great work which has now grown into the Uganda Church. It was long before then, as we see, that a little black boy was born of very poor parents in a small village, about forty miles from Mengo, the then capital of Uganda. He was one of twins. In that heathen land the birth of twins caused these people great fear. The name of the mother was changed. The children were dedicated to the heathen gods. There was great feasting and drum-beating.

As a boy of about eleven years of age, Apolo remembers well the arrival of two strange white men, who were said to come out of the earth. Others said they had come down from the sky and had tails like cows. It was about this time that Apolo made his first visit to the capital of the country. The early Missionaries had told the story of Jesus Christ, and many were believing that story. Their King, Mutesa, was a cruel tyrant; he would have his people killed for the merest whim. When he found a number of the boys and young men believing this story, he started a bitter persecution.

When in the capital Apolo found Mackay, the Christian Missionary, and learnt from him of the great God of Love, and how to read.

Apolo soon began to realise that he himself was a sinner, and needed a Saviour. There was a war on, and he had been compelled to join with the soldiers in the camp. One night, when all was quiet, he crept out into the darkness, away from the blazing camp fires, and there he sought God with all the longing of his young heart. In the quietness of that lonely place, he called upon Jesus to come to him. "Then," he says, "I felt some Presence with me, and knew that Jesus had heard me, and had come to seek me." Feeling he could not go on with the army and their cruel fight, he escaped into the forest in the darkness of the night. He wandered on towards Mengo until he met a small company of Christians, who were also fleeing from the persecution.

One night he found himself with a number of others in a hut close to a big cattle kraal. He was trying to pray to God when one of the men came to him, and said: "Do you know this Book?" "Yes," he said, "this is the Book that talks about Jesus. Can you read it to us?" It was one of the Gospels in the Swahili language. The man to whom it belonged had learned to read. They all sat found him while he not only read, but translated the words into their own language.

What a happy time this was for Apolo. He preached his first sermon in that little grass hut. After this, to his great joy, he met another man who had a Book in the Luganda language. This was his own speech, so, of course, he understood it better. Night after night, by the light of a flickering camp fire, he learnt more from this Book.

Passing through many years of much difficulty and persecution, he sought to learn more of the Christian faith, and to give his life to the service of Christ for his fellow-countrymen. At last the day of his baptism came, and on the 10th of January, 1895, he openly took his stand as a member of the Church of Christ, and the servant of Jesus. For his Christian name he chose Apolo. Before this, his heathen name was Munubi. Immediately after this he went to his friend Archdeacon Walker and told him that he wished to go out as a teacher to the peoples far away from Uganda, who had never heard the wonderful story.

With his bright, happy smile and attractive manner, Apolo soon made friends among the heathen.

After this there was a great Missionary meeting in the Cathedral Church of Namirembe, the Central Station of the Mission. Two young men, who had just come from the country of Toro, told how the people there were longing for the news of the Gospel, and how God had opened the heart of the Toro people to receive His Word. They told of the King of the country who wanted to become a Christian, and who sent a message through them to the Baganda Christians. This story fired Apolo's heart. Directly after the service he went to Bishop Tucker offering to go to that country.

Securing some further preparation, Apolo started off on his great missionary tour. Carrying his few possessions packed up in a bundle, with his sleeping mat rolled round, he said good-bye to his friends, and started off on the two hundred miles walk to the country of Toro. It was a very dangerous journey in those days. There were lions and other wild animals to be faced, and great rivers to be waded through, but he arrived there safely.

The first thing he had to do was to try and understand the language, which was different from his own. He very quickly succeeded in this.

He was welcomed by the young King. This King had recently been to Mengo, the capital. He had been baptised in the name of Daudi. On his return to his own country he began in real earnest to try to live the Christian life.

In a letter he wrote to "The Elders of the Church in Europe," he said: "God our Father gave me the kingdom of Toro to reign over for Him, therefore I write to you, my brethren, to beseech you to remember me, and to pray for me every day. ... I praise my Lord very much indeed for the words of the Gospel He brought into my country, and you I thank for sending teachers to come here to teach us such beautiful words. I therefore , tell you that I want very much, God giving me strength, to arrange all matters of this country for Him only, that all my people may understand that Jesus Christ He is the Saviour of all countries, and that He is the King of all kings."

It was a great opportunity for Apolo, and he made the most of it. An extract from his own writings tells us how he felt when he started this new venture:

"When I reached Toro at last, my joy knew no bounds. Could there ever be such joy as this, to tell the people who did not know, the wonderful story of Jesus, how He loved us all and how He saved us by His death upon the Cross? I had never known such joy as this that had come to me now, as I preached the Gospel to the heathen Batoro. God filled my heart with His joy."

In the land of Toro there is a mighty snowcapped mountain called Ruwenzori. Apolo had not been long in the country before he determined to climb it. It was not just that he wanted to see the wonders of that mountain, but he told the King: "I must see what is on the other side." Strange stories had come of wild people living in the country beyond. It was a hard climb, and so cold that most of his companions left him, but he continued until at last the great vision of the country beyond lay stretched before him.

He tells us the story himself of what he saw: "I saw the great country stretching out into the distance before me, most of it black with forest, and far away a range of hills that the guide told me was the Mboga Country, where lived many, many people. Something seized my heart and gripped me tight; it seemed to pull me towards those hills. A voice within me seemed to say: 'Over there in that country are thousands and thousands of people in heathen darkness; they do not know that Jesus loves them. Many of them live in that great dark forest where no Muganda has ever been; some are cannibals and eat human bodies, and some are the dangerous dwarfs of whom you have heard, who climb the trees to hunt; no one has ever been there to tell them about Jesus.' I knew at that moment that God was calling me! Toro had other teachers beside myself, while these people had none; who would go to them if I did not? Yes, I must go to them. T must go to them."

After Apolo had seen the church in Toro well established, he started on this other Missionary journey. For many days he climbed through the lower hills of the great mountain, and across the hot plains that divide the mountainous country of Uganda from Congoland. There was one great river, the Semliki, to cross, then he was in the country that he had seen from the mountain; between lay a great plain covered with long grass where many wild beasties roamed.

After Apolo had climbed the hills of Congo-land, he reached the country of Mboga, where he found very wild people. At first the King received him with kindness, hoping to get some presents from him. He gave him a hut and a little piece of ground.

As soon as Apolo could understand the language, he started to preach to the people. He told them of the great God, and of their own sinful lives. There was so much of witchcraft amongst them that Apolo told them it was the work of the enemy of man, and of God. The King and the people soon turned against him. They did not want to hear such teaching, but there was one poor woman who believed the story Apolo told her, and suffered much from a very cruel husband. This story that Apolo had to tell was a great comfort to her. She was baptised and became the first Banyamboga to enter the Christian Church.

THE witch-doctor of that country became mad with anger! He told the King that he must drive Apolo away, or his country would be ruined. The King was in real fear! He called his men together secretly, and promised a big present to any one who would burn Apolo's house down and kill him. Apolo tells us the story of the attack: "It was night-time, and I was alone in my house. I was praying to God, for I knew that I was in great danger. I did not fear, because I knew God would keep me safe in the midst of all my enemies. Suddenly I heard whispering outside my hut; I could not hear what was being said, but I guessed that my enemies had come to do me harm. Very soon I smelt the smoke of a fire drifting through the walls. Again I prayed with all my heart, and asked God to protect me. Once more I heard a voice, and this time it was God's voice, saying: 'Don't set fire to Apolo's house; he is My servant, he has come to do My commands.' It was all very wonderful, because the men outside heard the voice, and I heard them say: 'Who is that? Who tells us not to fire the house?' They were very frightened, for the flames were now roaring in the thatch of the hut. Then one of the men shouted to me from outside: 'Apolo, Apolo, are you in the house?

"By this time the flames had burst through, and I should soon be surrounded. I shouted back that I was praying. Then the men broke down the door, burst into the house, and some of them seized me, and dragged me into safety. The hut was a mass of flames, and was bound to fall soon. I saw a great company of men with their spears poised and ready for use, and in the other hand many of them had fire-brands; but no one touched me. They simply gazed at me in astonishment.

"Some of the men had dashed again into the burning house, and had brought out some of my possessions which they tied together with cords. Then, in great fright, they told me to take my things and fly for my life out of the country, for they were sure that the King would be very angry when he knew that they had failed in their task. To this I replied: 'If you wish to kill me, here I am, you may do so. Am I not alone before you all, and have you not got spears in your hands?' But the hand of God protected me, and they could do me no harm, but they told me to go with them to the King.

"When we got to his house he was waiting to hear the news of my death; and here I was, standing before him. He shouted to his men in great wrath: 'Why have you not done as I commanded you?' They could only reply: 'We were afraid because we heard a voice which said to us: "Apolo is my servant." We think it was the voice of Apolo's God, so we have brought him to you.' The King was still very angry, and commanded me to sleep at Semliki that night, and go to Toro the next day. I told him that God had sent me to Mboga, and that I could not leave unless He sent me. I then left the King and went back to my burning hut, but found that nothing remained but smoking ashes. The next day I began to build another hut."

For a short time Apolo was left in peace. The old enemy, however, was busily at work. Another order was sent to Apolo to leave the country. He says that when this came, he had just been reading about Jesus sending forth His disciples to preach the Kingdom of God. He was sure that Jesus must have known the difficulties and dangers they would meet, and He said to them: "Lo, I am with you alway," so he could not disobey His Master's commands, and he replied: "Go and tell your master that God's messengers were often killed in days gone by, but it did not stop other messengers taking their places. Tell him I cannot leave."

This made the witch-doctor and the King more angry than ever. They sent and had him bound with cords. When he was bound, Apolo said to his captors, "Let us sit down for a little while because I am sure God sent you men to me to be taught. You do not know how good He is."

This made the men who bound him feel what a wonderful man he must be. As they listened to his story, they came back to the King, saying: "Apolo is doing no harm. He is only teaching the people that God loves them. We could not bring him."

This time the King sent his Prime Minister, who came and called out to Apolo: "Come out, the King has sent me for you." "Yes, I will come," said Apolo, and once again he was led to the King.

When they arrived at the King's quarters, they found him sitting on the raised platform at the entrance to his house, waiting to try the case. He at once addressed the prisoner: "I have sent several of my men to you telling you to leave my country; you have refused to obey me. Now tell me the reason why you have not gone." Apolo replied: "I also have a Master, and His Word is my law. He sent me here to teach your people, and until He tells me to leave I will not go willingly.' "Well," said the King, "if I allow you to stay here will you give me your promise not to teach my people to read that Book, and that you will not try to persuade them to disobey my orders when I send them to raid the Balega? "

Apolo promptly answered that he couldn't obey such an order, but that he must do the work God had sent him to do.

At this the King became more angry still and told the men around to strip off his, clothing, and thrash him. After suffering this very brutal punishment, Apolo, weak and trembling, was driven back to his house. There he lay for days, suffering terrible agony, but praying every day that he might be restored to go back to his work. As soon as he was able, he went back to the Church, and gathered the little band of Christians together. For a few days he was able to continue his teaching. However, as soon as the witch-doctor saw that the people were going back to Apolo, he stirred up the King and the cruel men around the court. They went and seized Apolo again and dragged him before the King. This time they really did mean to kill him.

Lash after lash fell on his poor naked body, until he became unconscious. The King told them to drag his body away, and throw it into the long grass, where he was sure he would be destroyed by the wild beasts.

The King now thought that Apolo was dead, and that he would not have any more trouble, and he determined to make a great feast. There was much drinking and feasting, and they thought they had banished the teacher and his Book for ever.

There was one of Apolo's, friends however, who was watching in the distance. This was the old woman who had been baptised. Her beloved teacher had been killed before het eyes, and thrown into the jungle! After a little while, when she thought it was safe, and she could go secretly, she followed the track where the body had been dragged, until at last she found Apolo lying apparently dead. She knelt down and wept I To her great joy, there was a movement. She was sure be could not be quite dead.

Quietly she went off to a stream to get some water. As she bathed his wounds, she found he really was alive. It was too far to her own home, and if she had tried to carry him there, she would have been discovered. Finding a little ruined hut, with great difficulty she carried Apolo there. He was still unconscious, and could not help himself. She gathered soft, fresh grass and made him a bed, then some sticks for a fire, and closed up the entrance to the hut.

For weeks she continued to nurse Apolo, and feed him secretly. He became conscious, but was so injured that he was helpless for a time. After about six weeks of this faithful, secret nursing, Apolo thought he would be well enough to go back to his people. The woman urged him to go back to safety in his own country, Uganda. No, he could not do that. God had more work for him to do, and he must do it!

The King and his people thought Apolo was dead and done with. They went back to their heathen ways, never expecting to be troubled with him again.

EARLY one Sunday morning, as soon as Apolo felt able to do so, he returned to the little village church. He beat the drum which for so long had been silent. Immediately the whole place was in a turmoil. The King, hearing the drum, became terribly frightened. He sent out to find who was beating it. The messenger returned with the exciting news that it was Apolo himself, alive from the dead. He was calling the people to prayer.

The King would not believe this, and decided to go and see for himself. As he came near the church, he was more alarmed than ever to hear the sound of voices, one of which he was sure was that of the man whom he had killed.

The King crept up to the door of the little church, and there, to his amazement, he saw Apolo with a small crowd of awe-stricken men and women around him. Apolo was sitting in the midst, with his little Book in his hand, reading to them the wonderful story.

When he saw the King, he went to meet him and greeted him with a happy smile, and asked him to come into the church and join in their class.

To the surprise of everybody, the King came in, kneeled before Apolo, and begged him to forgive him the great sin he had committed. Apolo took the King's hand in his own, and kneeling down by his side, he called upon all the people to join him in prayer.

What a wonderful scene that was in that little grass sanctuary. From that day the King, from being the cruel tyrant, became the best friend of Apolo. After great effort, he learnt to read the Book himself, and was baptised, taking the name of "Paul." It was a day of great rejoicing for all Mboga when "Tabalo" the King, became "Paul" the Servant of God.

Now that the King was a Christian the persecution ceased, and the people were not afraid to attend the church, it was soon crowded out. The people with one accord set to work to build a better one. Apolo rejoiced in this wonderful change that had come over the King and people, and sent a call to Toro for more teachers.

After the great success which followed the striking conversion of the King, Apolo was advised to go to his own country for a little rest, and to recover his health. He had not been long there when a terrible story reached him, that a neighbouring tribe had attacked the Mboga people, and that many had been killed. This news came as a great grief to Apolo, and at once he made plans to return, even though it meant facing death.

The messenger who brought the news told a tragic story. Men, women and children had been killed in their houses, for before they could get away the houses were burned over their heads. Over two hundred of his faithful people had been killed, including several of the teachers.

Before Apolo left Toro a special service was held at the church, at which he preached. With tears streaming down his face, he cried out in his bitterness: "Are these not my children for whom I have suffered? Did not God give them to me? Are they not in deep distress? I must go to them quickly, to help and comfort those who may be left. Once more God's House must be built." It was an appeal which no one who heard it could ever forget. At the end of 1911 Apolo was back amongst his people.

Blackened ruins were on every side. Familiar faces were missing. As he and the King met, the King said with emotion, "Thank God for bringing you back to us. Bat what sorrow we have seen. Look at the ruins of our church which was built for God. All is done! How can we ever read again?"

Apolo told the King and people that he was still their helper, and they would soon rebuild the church. Soon they were busily at work. The Church of God was once more established.

Now that God had given such a triumph over the cruelty of the enemy, and the church was growing in numbers and influence, Apolo began to tell them of the wild people still beyond the reach of the Gospel. They talked of the great forest, which, though so near to them, few of the people had dared to enter. They had heard of the wild and dangerous little folk called the "pygmy." There were other wild folk, including the Bambuba--wild, naked people of whom they had heard gruesome stories of cannibalism.

It was indeed a difficult and dangerous proposal for these people to carry the story of God's Love to these wild folk. Apolo, however, was never daunted.

Apolo's courage called forth volunteers willing to go with him into this dangerous country.

After some time they found these little folk, and were able to make friends with them. Apolo and his companions learnt all they could about them, and their ways of life, until confidence had been gained, and the teachers that Apolo had trained were able to live and travel through the forest with them.

It was a strange and weird experience, but kindness won. The little folk began to respond to the teaching, and listened to this wonderful story of the love of the great God, and Jesus the Saviour.

Mboga is now a small Mission station about twenty miles west of the Semliki river, situated on a high hill about 1,300 feet above the river. It is also the name of the country occupied by people called the Banyamboga, a Lunyoro-speaking people akin to the Batoro. Originally the district lay within the sphere of British Uganda. In 1910 the boundary line was moved to the Semliki River itself, and Mboga became Belgian Congo territory. It says much for the people of this district that though they are now so isolated from contact with the more civilised peoples in Uganda, they still retain their own preeminence.

HIDDEN away in the forest the pygmies do not often see the rainbow. When they do, they have great dread of it.

They call it "papse," meaning "father." He is a great snake climbing from the water to the sky. Some tribes of the pygmies are called Baka. They are supposed to be especially wild and ever on the move. Others are called "Atikitiki." I have often heard the tribes, especially the Zande tribe, calling them by that name.

The pygmies are very fond of dancing. To the sound of their drums they add bones, tattles and singing. They can keep up their twisting and turning for hours without showing tiredness. Their tunes and their dances are very much like those of the other forest tribes. Sometimes the music will stop suddenly, the dancers will stand stock still, staring up into the sky, their heads, necks and eyes seem to be straining every nerve. Suddenly the dance starts again!

Amongst the monkeys of the forest there is the chimpanzee. One of their dances is supposed to represent this monkey. Only men and boys can take part in it. With slow, twisting movements and weird grimaces, they go through the camp. The eldest of the group, armed with bow and arrow, represents the hunter. He lurks behind the bush or tree, and takes aim at the other dancers. Off goes the arrow. The dancers scatter, roll about the ground, grin and roar. This they will continue doing for hours.

In their fetish worship they use a kind of whistle, which they call "piki-piki." It is a round piece of wood about the thickness of a man's finger. They burn holes in the ends with red-hot irons. If they wear it, it is believed to be a safeguard against their enemies or strangers.

They also use a bit of whirring wood. The sound, they say, is the voice of Tore, one of their ancestors. It is used to terrify disobedient women. If a wife is sullen or quarrelsome with her husband, but especially if she bites him, the ominous sound of the whirring wood is heard at night-time near her hut. She knows then that she must expiate her crime. She sets off into the forest with all speed, and goes to her own clan the next morning and begs for a gift, which she offers as an atonement to her husband.

The pigmies have a very clear idea of the mother-in-law problem. Mother-in-law and son-in-law must not even talk with each other. The relationship of father-in-law and daughter-in law is not quite so rigid.

The pygmy does not indulge in the luxuries of bathing and washing. When he awakes, his only toilet consists in rubbing his eyes.

He is an early riser, and will have his fire lit before dawn, and as soon as it is light enough the forest will resound to the call of the huntsmen.

The Bambuti hut is very much like the half of a large egg. It is actually a branch-topped roof roughly thatched with large leaves. There are numerous clans, sometimes distinguished as "Adzapori," who may be called the village people, as distinct from the forest people, "Basua wa pori."

Herr Schebesta says:

"Just off the motor-road from Irumu to Beni, which has recently been extended to Ruanda, in the territory of the Bambula, there are large numbers of pygmies. I spent a whole day amongst those attached to the village of Mwera. Mwera himself, a Munande chief, had under his control the Banande and Bambula as well as a considerable number of pygmies.

"The pygmies are called Awasomba by the Banande, but they are known among themselves as Bapakombe or Wamba as well as Bambuti. They speak both Efe and Kibira. Incidentally it seems that the word Bambuti belongs to the Kibira tongue and is probably derived from "gbutiu" (little). I noticed that the Mwera pygmies hang little bundles of foodstuffs from the branches of trees, after the negro fashion, to protect themselves from reptiles and rats."

The Mwera Bambuti lived almost on the fringe of the plateau, which slopes down to the Semliki River.

To the passing traveller the dense forest may seem almost uninhabited, or even impossible of habitation, yet it may be in certain districts swarming with these little folk. For hours, and days, they will pass through the forest watching some caravan, and yet their presence never be suspected. In passing a group of their little temporary huts, evidences of their fetish worship may be seen, a few sticks in the ground with a little grass roof.

In a gable-roofed hut are placed the sacrificial offerings for Kalisia. Against this structure the pygmy props his spear at night, and appeals to the deity to give him luck in the morning's hunt. And as he steps confidently through the forest on the following day, if he feels something brush against his shoulder he knows that Kalisia is telling him to be on the alert, as there is splendid game right ahead of him.

Before lying down at night the pygmy puts an arrow under his head. If he dreams that he will kill an animal, it is a hint from Kalisia which he follows up without demur the next day, as he knows that he will return with a good bag.

LET me now tell you of some of the things that happened when I met Apolo. I have met him several times. Apolo was my warm-hearted friend. On one occasion after many days' travel I had crossed the great plain which separates Uganda from the Congo, and which Apolo, we remember, saw from the mountains, and was climbing the hills to Mboga. It was about mid-day, the sun was very hot; I was feeling very tired, and not quite sure of the right path. Coming round the bend by a big tree, I saw a black man standing by it. He was almost the first one I had met that morning, and I was just passing him when he pointed to something at the foot of the tree. Looking round, I saw a banana leaf, which you may know is a very big leaf. As I could not speak his language, I did not know what he meant. Then he lifted the banana leaf, and I saw a little bottle of milk and some bananas. By this time my black boys had caught me up, and I was able to find out that these had been sent by Apolo to cheer the tired traveller. It was most thoughtful of him, and I just sat down and finished them off.

This black man now became our guide. A few more miles on and I saw a big plantation with grass-roofed houses, one larger than the rest. This proved to be the Church of Mboga. Apolo and many of his people came out to meet me. His cheery, shining face told how happy he was in the service of Jesus Christ. He took me beyond the church and showed me a little grass hut, beautifully finished with fresh grass. This he had prepared for my coming.

That week-end was a memorable one, as I spent it with Apolo and the members of his church. I was also introduced to Paul, the one-time cruel King who tried to kill Apolo, and who afterwards became, as I have told you, his sincerest friend and helper. What a joy it was to see these two men, both heroes, walking hand-in-hand as we left the crowded church on that Sunday morning. How truly "Tabolo the persecutor" had become "Paul, the friend of Jesus, and Apolo."

After that week-end I started off on a march for five hundred miles through the forest, trying to find some of the many tribes who had never heard the story of Jesus and His love.

A few years later I had the great joy of visiting Apolo once again. This time in the company of Archdeacon A. B. Lloyd, the English Missionary who had been the guide, counsellor and friend of Apolo during most of these years in the Congo. Archdeacon Lloyd was Superintendent of the nearest Mission Station in Uganda, that of Toro.

We had motored together from Uganda till we reached within forty miles of Mboga, when the road, or rather track, just ended! We could not drive the car any farther. From this point we had two days' march, twenty miles a day, before we reached Mboga.

It was a very rough walk over hill and dale. At the end of the second day, many miles before we reached our destination, we met parties of the young men who had been sent out by Apolo to welcome us. What a bright, happy crowd they were. It was their great joy to welcome their old friend and "father," Mr. Lloyd, whom they had not seen for some years. Then, a few miles before the end, we met Apolo himself, with his usual beaming countenance.

What a welcome we received! It was dark by the time we reached Mboga, but we soon saw what a kindly preparation Apolo had made for our hospitality. No white friend could have been more thoughtful. Gifts of food of all kinds were brought. Chief Paulo himself came along, bringing a fine, fat-tailed sheep.

After sundown the church drums boomed forth the call to prayer, and the church was soon full for evening worship. It was an inspiring end to a great day.

What a Sunday that next day was, with its crowded church services. In the morning there were almost as many people outside as in the church.

The Archdeacon preached at the morning service; one felt indeed the place was a real Bethel, a House of God. We met many of the young men, and women also, who, like their teacher, had dedicated their lives to the spreading of the good news of salvation.

There were more than fifty of them who had come in from their far-distant posts to welcome Mr. Lloyd. Some of them were living amongst cannibal tribes, and had stories to tell of the wild scenes they had witnessed. Others had come in from the great forest where they had been travelling about with the pygmies, seeking to tell them of the love of Jesus.

What an inspiration it was to hear the experiences of some of these young men. Amongst the young women was the daughter of the chief himself, who was now encouraging the young people, including his own, to dedicate their lives to the service of Jesus.

That Sunday was Passion Sunday, March 25th, 1928. What a glorious morning it was, with the fresh, sweet air sweeping down from the snowy mountain, Ruwenzori, that shone so brilliantly the other side of the valley. Its great snow-covered peaks glistened like crystal in the sunshine. As early as seven o'clock crowds began to collect round the church. It was packed long before the hour of service. The waiting time was passed in quiet and reverent hymn-singing.

As Mr. Lloyd and I entered the garden plantation in the midst of which was the church, we found an orderly crowd seated around it. They could not find room inside the building, but were determined to enter into the service. They had books, and many were quietly reading.

By this time Apolo had been made a Canon of the Cathedral Church of Namirembe, as some little recognition of the great work he was doing for the Kingdom of Christ.

And now Canon Apolo as he led us into the vestry prayed for Mr. Lloyd: "Our father has come back to us, and we thank Thee, O God; may he speak to his family the words that Thou hast given him, and thus lead many to our Saviour Christ Jesus." Truly this prayer was answered, as the Spirit of God moved over that vast and earnest congregation.

This service was followed by a Communion Service, to which over three hundred people stayed. The service was beautiful in its glorious simplicity, as it was conducted by Apolo. Mr. Lloyd himself has told us: "Something happened at the service that none of us who were present could ever describe. Undoubtedly there was the Presence of One in our midst that made our hearts burn within us as we left that sacred place, where we had once more met with the Lord Himself."

ON the Monday morning we started off for the heart of pygmyland. We were to travel many miles along the narrow paths that led from Mboga right into the forest. Now I was to have the joy of another visit to these forest dwellers, this time in the company of the Rev. Lloyd and Apolo.

With the first rays of dawn next morning, our porters arrived. Kit was prepared, and we set off for the march into the Pygmy Forest. Crossing the hills rising to the west from Mboga, a magnificent panorama presented itself of the Semliki Valley, and the mighty range of the Ruwenzori snow-capped "Mountains of the Moon"--the snows that eventually water the thirsty land of Egypt, three thousand miles to the north. After about ten miles' march, we entered the great forest itself, passing from the open sunlit panorama to the gloomy shades of this primeval wilderness. Another five miles march brought us to the village of Bedo, where we were to camp for the night.

Near this village we saw the first of the little friends we had come so far to visit. We were standing at cross-roads in the forest when we suddenly found a diminutive figure, who apparently appeared from nowhere, standing by our side. He was about four feet in height, beautifully proportioned, and presented the appearance of a little gentleman of his race, though in nature's garb.

Showing us the way, we plunged for a short distance through the tangled undergrowth of the forest, and emerged at a small clearing to receive the welcome of the first little colony of Bambuti, the pygmy tribe of these forests.

When they caught sight of us, they ran forward shouting "Itiri, itiri!" "Welcome, welcome!" What quaint little folk they were, wild, weird wanderers through the recesses of some of nature's gloomiest regions. There they wait in the dark for the dawn of a day which they cannot, as yet, comprehend. They are verily outcasts from society, representatives of former tribes driven into the dark forests by the coming of the Bantu, and other races, millenniums ago.

At the end of that first day's march we camped at the edge of the forest, amongst the Bakonjo people. They were people amongst whom Apolo had been working for many years. One of the teachers from Mboga was in charge, and lived in a little hut with his wife and small children. Crowds flocked to the church for a service of welcome. The blowing of horns, and the beating of drums, told them the white men had arrived. Gifts of food were brought, and the people of the village indulged in a frolic of real joy at the coming of the white men.

At sundown the little church was packed out with worshippers. What a quiet and reverent company they were as they knelt to pray!

Next day, after a long march through the forest the pygmies led us to their camp. It consisted of little huts made of twigs and thatched leaves. In the centre of the group of leafy huts there was one much bigger, and better built, with two little sticks tied together on the roof, to form a rough cross. Into this our little friends invited all who could enter. It was a very tiny building. A teacher from Mboga, who had been a real Missionary to these folk, read a short message from the little book that Apolo had prepared in the pygmy language, telling them some news of the Gospel. All joined in the family prayer. On either side of Apolo knelt a little pygmy with upturned face, looking into his eyes, and repeating that grand prayer: "Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be Thy Name."

It must have been a sight to cheer the angels in heaven! When we came from the church Mr. Lloyd asked one of the pygmies: "Do you pray to Jesus now you have heard about Him?"

"Yes," he replied, "I do."

"What do you pray for?"

"O, sir, I do not know what to pray for, so I just pray; He knows what I need, I don't; it's all right."

The following morning, escorted by a friendly little guide and Apolo, we plunged deeper into the dark places of the great primeval forest, visiting more colonies of pygmies. We were able to see them just as they live, hunting through the forest, and to spend the nights camped with them in that wild, weird country.

We must have met more than 250 of these little people altogether, in the various troups that we visited.

IS there a universal pygmy speech, or a speech with varying dialects? It would need much more investigation before finally settling these problems. So far as we know at present, the pygmy folk living in the northwestern area between Nepoko and the Bomokandi River make their principal centres at Medje, Babeyru and the Majogu.

Southward of these, the Bambuti occupy a very considerable area, and they are closely allied in friendship with the tribes of the Babali, Bandaka and the Barumba. The name Bambuti, originally applied solely to the Kabira-speaking dwarfs.

The pygmies do not seem to be able to count beyond two or three, though sometimes they seem to manage up to ten, by using fingers and toes as other tribes do. They are good linguists, in the sense that they can generally carry on conversation with the ordinary tribes around them. They seem to have three languages, Beta, Medje, and Efe.

This latter language seems to be used as far eastward as the Ruwenzori Mountain.

These Aka, as well as the Badike and a considerable portion of the Balika and Wabuda pygmies, speak Medje, which justifies the grouping of all of them under the heading of Aka.

"The Baleu pygmies, whom I met," writes Herr Paul Schebesta, "in the middle reaches of the Ituri, not far from Panga in the village of Mokope, should also be numbered among the Aka. Unfortunately I saw there pygmies, who live in the extreme west, under conditions very unfavourable for a detailed examination of their customs, and standard of living. A terrific thunderstorm burst overhead just as a deputation from them called on me. I had only succeeded, before they left late at night, in establishing the fact that they belonged to the Aka, although they recognise the Wangelima, in whose territory they live, as their patrons, and are called Basangu by them. Their camp speech, which, like the Medje, has a large admixture of words from other languages, is very curious. The Supreme Being, whom they call 'Nabagwa,' is known among the other Aka by the title used among the Medje, while the Baleu use the term 'Barumbie.' They say he causes the thunder by tramping on the sky. He is the creator of all things. They call him 'Our Father.' He existed from eternity, and he has no wife.

"The skill of the pygmies as linguists impressed me very much. Some of them spoke Kibango (Kibira), while others spoke Kilese, the language of the far-off, north-eastern region on the other bank of the Ituri. Of course, there were also just a few Mambuti in Avakubl who could speak Kilese. The versatility of the pygmies of Kayumba was also shown in the wide range of melody which their songs exhibited. This characteristic I noticed especially in their performances on the flute, of which I took gramophone records. Their extensive musical repertoire is probably due to the influence of the negro tribes, the Balese and the Babira. Speaking generally, I noticed that all pygmy songs and dances, in all parts of the Congo forest region, have definite common characteristics which keep recurring, and which make their individuality. The little troop of about five or six women--four of them pygmies, that walked right behind me, started a melancholy sing-song. It was a sort of litany in the Bandaka dialect of which I did not understand a word, and it fascinated me by its persistent monotony. I was just listening to the tune, when a pygmy behind me whispered: 'Muzungu, do you understand what they are singing?' I caught the word 'Asobe,' which cropped up again and again in the chorus. One of the women sang alone for a bit, and then the rest joined in the chorus. The song lasted for a very long time. When it ended I asked what it was about. Apparently the precentor always kept varying the same theme in different tones. She kept calling 'Asobe' (God) to protect them, and see them safely home. The gist of the song was that morning had come, and if God protected them against all harm during the day, they would reach their village in safety.

"This primitive, sincere and simple morning song, chanted in such a desolate elemental environment, impressed me very much. From a psychological point of view, I could appreciate the emotion which prompted the song. There they were--just a mere handful of tiny women, alone and unprotected, travelling through the gloomy, dripping forest with utter strangers, most of whom belonged to the dreaded Wangwana tribe. It was a situation calculated to stimulate an eerie feeling!

"I heard one such legend time and again in various widely distant places. Told in the quaint idiom of the Bambuti, it shows that the latter regard the chimpanzee as a sort of pioneer of civilisation.

"In ancient times a pygmy, while out hunting one day, came upon a chimpanzee village. He was astounded at the many strange things he saw, and at once returned home and reported his discovery. Accompanied by a negro, he set off again. The first sight that met their eyes was a magnificent plantation, abounding with green trees that were laden with bunches of golden bananas. At first neither of the two ventured to touch the beautiful ripe fruit. They had never seen anything like it before, and for all they knew it might be poisonous. Then the wary and cunning, negro urged the pygmy to taste one. He pointed out to him that he was in the habit of eating many different kinds of wild products of the forest, and argued that, as none of these had ever done him any harm, it was scarcely probable that this new discovery would be injurious to him.

"The Bambuti gazed longingly at the luxurious festoons. At last he took heart, and, somewhat timidly, ate a banana. He announced that it tasted delicious. The negro watched him enviously, but was afraid as yet to touch the fruit himself.

"When evening came, they both lay down in the chimpanzee village; but, for the negro, it was a sleepless night. He was still unconvinced that the fruit was not poisonous, and kept fretting about the dwarf, although the latter was sleeping soundly.

"Before dawn the negro aroused the pygmy, and asked him how he felt. The little chap rubbed his eyes, replied that he had never felt better, and at once resumed his eulogy on the flavour of bananas. The negro had no further anxiety. Back they went to the plantation, and had a hearty breakfast on their new-found fruit.

"Suddenly the thought struck the negro that it would be an excellent idea to grow this delicacy in his own village. The Mambuti fell in with the suggestion, and they set to work at once. While the dwarf collected the most luxurious clusters with the intention of sowing the fruit in the earth, the negro, to the intense amusement of his small companion, broke off branches, which he took home and planted round his hut. The dwarf, on the other hand, laid row after row of bananas in the ground. The very next morning the negro's shoots drooped and withered. The pygmy laughed heartily at the man, and, for some time, kept taunting and teasing him for his silly whim. But the negro was cunning, and let the mannikin have his little joke.

"The pygmy waited in vain for his bananas to sprout. Eventually he dug up the ground, and saw that the fruit had become rotten. However, he consoled himself with the thought that the negro had had similar bad luck with his branches; so he took his bow and arrows and resumed his quest of game.

"When months later he returned to the negro's hut, he could scarcely believe his eyes. A luxurious banana plantation had grown around the little dwelling. Now was the negro's turn to laugh, but the pygmy, concealing his annoyance, remarked diplomatically: 'I knew I had not the stuff for a farmer in me. That's more in your line, I prefer to stick to my hunting. You can go on planting, bananas, and I shall eat them, for it was I who introduced them to you.'

"The frontier Banande call God 'Muema.' His home is in the forest, and they never fail to give him thank-offerings of game, fruit and honey.

"The further one travels from Beni towards the Ituri, the more one finds the name Kalisia applied to the deity, instead of Muema. The Babira assured me that Kalisia was exclusively used by the Bambuti. From Kalisia I was told all good things come. He is gracious towards the Bambuti, while the Babira dread him. He stands by the hunter when he is on the trail of game, inspires him regarding the proper place and time to seek his prey--in a word he drives animals across his path. Standing behind the pygmy, as Horns of yore stood behind Pharaoh, he bends his bow and inspires his arm, so that he may not miss cither elephant, buffalo or wild pig. Kalisia always gives him a hint, too, about days which are likely to be unlucky for hunting. On such days the pygmy squats by the fire, or loafs round the camp."

Herr Schebesta tells us that so far, with the exception of Apolo's little pamphlet, nothing has been printed in any pygmy language or dialect. As no European scholars have paid any attention to the subject, it occurred to him that readers ought to be interested in this specimen of the speech of the little men of the Congo. It is the Lord's Prayer:

"Amu afu hocha halu tida, na hitu habula fua, oka nibai habula fua, osani nibai habula fua halu tida bai hene. Eti anu amubai amuhanu obala, au au amubaie, amuahenue ode amue ahesimagu ledeai, nagitsu amue idere anue nedo uda eda."

The Mbuti language spoken by these pygmies is quite distinct from Konjo, the language of the Bantu tribes, amongst whom they live. These Bakonjo lads have the Gospel of St. Mark, published by the British and Foreign Bible Society--a volume they greatly treasure.

A NUMBER of the young Christian lads of the Bakonjo tribe have been trained by Apolo. They have learned the language of the pygmies, and are now actually living with them, travelling through the forests with them, seeking to befriend and teach them.. We saw groups of these pygmies squatting on the ground, in the dark shades of the forest, around the little ABC chart with one of these young teachers in their midst, seeking to expound to them the meanings of sign, symbol and sound.

In some of the pygmy groups, these heroic young men have so far won their confidence and succeeded in teaching them, that we saw and heard these pygmies joining in songs of praise, and listening eagerly to the instruction being given. The message of redemption was being taught them in their own mother tongue. Probably one of the most thrilling visions one could have, even in this land of Africa where so much is weird and romantic, was that scene where Apolo, standing in the midst, surrounded by one of the larger colonies of pygmies, was teaching them to repeat the Lord's Prayer. After such evidence of the power of the grace of God, we need despair of no community as being beyond the reach of His love.

On the last day we visited another colony, where no teacher had, as yet, been placed. Apolo was bringing a messenger to them. As soon as our party came in sight of the colony, they crowded around us. No signs of fear! Apolo's presence was sufficient assurance! Sitting on a fallen tree-trunk, we listened and watched as Apolo, through the interpretation of one of his teachers, told them why we had come to visit them; told them something of the great story the teacher he was to leave with them, would explain more fully; spoke to them something of the wonders of reading the book.

Squatting on the ground facing Apolo was the chief, or colony father. Others crowded round him. His wizened face and sharp, beady eyes gazed up into Apolo's face. He seemed to know just what was being said. Now and then he gave a nod and a knowing glance to his people. He and his folk well knew of the teachers who had gone to live with the other pygmy colonies. Apolo's fame had travelled far into these forest seclusions. He was known far and wide as their friend. Now they were to have a teacher of their very own! When the chief realised this happy fact, his face beamed with a joyous smile.

It was getting late! We still had a long march before camping. We said farewell to these little folk and their teacher. Soon we were lost to each other by the dense bush.

The last vision we had of this brave young teacher lad, not more than fourteen or fifteen years old, was as he stood surrounded by his pygmy friends gazing at us when we resumed our march. Here was a true Hero of the Cross!

Apolo was a man of prayer, of a simple child-like faith which just accepted God's promises. He had many difficult problems to deal with. Often when he was talking about them he would stop suddenly, and say quite naturally: "This beats me. Let us pray about it." At once he dropped upon his knees, as a child speaking to his father, and asked God to make things clear to His children, certain that the prayer would be answered.

As year after year went by, Apolo kept steadily on with his mission of love and mercy amongst the people of Mboga and the wild forest regions, winning more and more to the Faith of Jesus Christ. While able he took long journeys, some of the young men whom he trained as teachers and evangelists going with him.

His name was carried far and wide, as that of a great-hearted man of themselves who loved everybody.

BISHOP WILLIS, of Uganda, in whose diocese Mboga is situated, paid a visit to Apolo recently, that has been so well described by Mrs. Willis that the story is another revelation of the grace of God working in and through this African Apostle. She says:

"We reached Mboga in the Belgian Congo after a long day's march, as the dusk was gathering, on the evening of Saturday, August 1st, and were met by a crowd of enthusiastic little schoolboys lined up on each side of the path, with their teacher, Ruben Kakonge, the son of our late treasurer in Uganda. Bunches of flowers were tied on to the ends of long wands, and as we reached their ranks, they gave three resounding cheers for the Bishop. It was too dark to see the faces of the men, women and children, who greeted us warmly, as we proceeded down an avenue of trees, past the church, to a little round rest-house, built by Apolo, for travellers. When we entered we found clean white matting on the floor, camp chairs around the table, on which was a jar of flowers, and some photos of Missionaries, and a religious picture kanging on the walls. There was an air of neatness and orderliness pervading it all, which we found afterwards was one of the characteristics of Apolo. He, of course, was there to meet us, and sat and chatted, asking us how we had fared upon our journey from Toro, while our tents were being pitched on the ground, outside the rest-house.

"Next morning, being Sunday, we proceeded down the avenue of pretty flowering trees to the church for the Confirmation Service. The people were all assembled and there was a great atmosphere of reverence and attention throughout the Confirmation Service, when forty-six were confirmed, twenty-seven men and nineteen women. The son of old Chief Paulo (who had begun by ill-treating Apolo and ended by loving him dearly), was also being confirmed with his wife. They all came to tea with us afterwards: Paulo had a particularly nice face; his son, who is now chief in his father's place, his wife, Apolo, and Ruben. Apolo's face was beaming as it usually does, radiating goodness. He was telling us how he taught the people to work with their hands. I asked him if he did that first of all, or whether he taught them to read first. He said, 'First of all I teach them religion and how to read. I nearly broke myself teaching that old man to read,' pointing to Paulo, who quite enjoyed the joke, 'and then,' he said, 'I teach them to make roads to plant trees, and to build houses.'

"Everything we saw at Mboga is, of course, the result of Apolo's work. He told us that he first became a Christian from hearing of Christianity through another Muganda Christian, and then he learnt to read the Bible for himself. Only a peasant, with no educational advantages, he is a leader among men, wherever he goes, loved and trusted by the most primitive tribes among whom he travels, including the pygmies of the forest, with whom he eats and sleeps in their tiny huts. Apolo is evidently much respected by the Belgian officials, who consult him as to the people among whom he works, as we witnessed when the Belgian Consul came to tea with us on another day. If a primitive tribe proves recalcitrant, the Belgians send Apolo to tackle them. He wins his way with the people wherever he goes.

"On the Monday morning we started with Apolo for the pygmy forest, not to see the pygmies, as they had moved too far into the interior for us to reach them in the time at our disposal, but to visit another tribe, the people of which are allied to them, but not so small. As we entered the forest, we saw the deep holes in the mud, made by the elephants' feet, who had recently passed that way, and we heard the monkeys chattering overhead, but we saw actually nothing of the animal life. The forest was beautiful with all its thick vegetation, and a kind of hart's-tongue fern growing as high as our waists, and we travelled for miles along the narrow winding native track, impenetrable jungle on each side. There were very few flowers, but we passed one beautiful poinsettia bush, and here and there in marshy ground was a very sweet-scented creeping mauve sweet-pea.

"Sometimes the path widened out into what looked like an aisle, with the tall grey tree-stems looking like pillars in some vast cathedral.