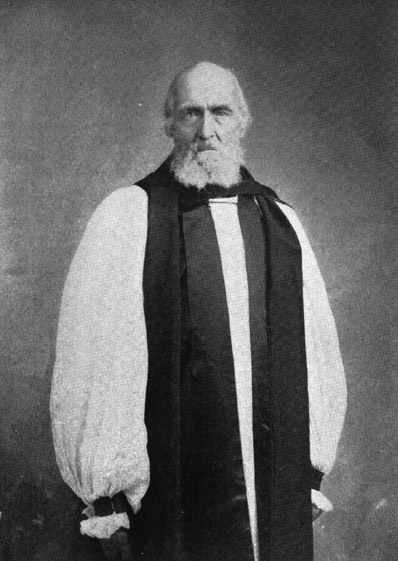

WILLIAM CARPENTER BOMPAS

by H. A. Cody

WILLIAM CARPENTER BOMPAS was born at 11 Park Road, Regent's Park, London, on January 20th, 1834. He was the fourth son of Charles Carpenter Bompas, Serjeant-at-law, one of the most eminent advocates of his day, and leader of the western circuit, and of Mary Steele, daughter of Mr. Joseph Tomkins, of Broughton, Hants. Serjeant Bompas, it is said, was the original of Charles Dickens' celebrated character, "Serjeant Buzfuz," in "Pickwick Papers."

In 1804 Serjeant Bompas died very suddenly, leaving a widow and eight children in poor circumstances.

William, in early youth, showed most plainly those characteristics which marked his whole life. He was a shy boy, owing partly, no doubt, to private tuition at home, which deprived him to a large extent of the society of other boys. Cricket, football, or such games, he did not play, his chief pleasure being walking, and sketching churches and other buildings he encountered in his rambles. Gardening he was fond of, and the knowledge thus gained stood him in good stead years later when planning for the mission-farms in his northern diocese.

The influence of a religious home made a deep and lasting impression upon him. His parents were Baptists, and William, at the age of sixteen, was baptized by immersion by the Hon. and Rev. Baptist Noel.

As a university career was not practicable, he was articled to a firm of solicitors in 1852. But after a period of seven years in legal pursuits his health gave way and he was obliged to give up his work altogether.

During his year of inaction the Greek Testament was his constant companion, and upon the return of his strength his mind reverted more and more to his early desire of entering the ministry. Leaving the communion of his early associations, he decided to seek ordination in the Church of England, and in 1858 he was confirmed by the Bishop of London, at St. Mary's, Bryanston Square. His remarkable linguistic ability enabled him soon to add by private study a good knowledge of Hebrew to that of Latin and Greek, which he already possessed.

In 1859 he was accepted by Dr. Jackson, the Bishop of London as a literate candidate for Holy Orders, and was ordained deacon by him at the Advent ordination the same year, after which he held several curacies in various parts of England.

But Mr. Bompas' mind had for some time been turned toward China and India, with their seething millions. He longed to carry the message to those far-off lands, but as he was a little over thirty years of age the Church Missionary Society thought him rather old to grapple with the difficulties of Eastern languages. But when one door closes another opens, and at the right moment Bishop Anderson arrived from Rupert's Land, and made his great appeal for a volunteer to relieve the Rev. Robert McDonald, at Fort Yukon. So stirred was Mr. Bompas by the address that after the service he walked into the vestry and offered himself for the work. He was at once accepted by the Church Missionary Society and ordained to the priesthood by Bishop, afterwards Archbishop Machray, who had just been consecrated successor of Bishop Anderson.

Mr. Bompas had only three weeks in which to prepare for his long journey. But they were sufficient, as he was anxious to get on his way. So complete was his consecration to the work before him that "he decided," so his brother tells us, "to take nothing with him that might lead his thoughts to home, and he gave away all his books and other tokens of remembrance, even the paragraph Bible which he always used."

On June 30th, 1865, Mr. Bompas left London for Liverpool, where he boarded the steamer Persia, bound for New York. He reached this latter place on July 12th, and proceeded by rail to Niagara, and thence to Chicago. By steamer and rail St. Cloud was reached, where the first difficulty presented itself. Since the fearful Sioux massacre of 1862, people were in great dread all over the country, and they found it impossible to get anyone to convey them towards Red River. After much trouble and delay, Mr. Bompas and his companions were forced to procure a conveyance for themselves. Before leaving St. Cloud they were told time and time again to beware of the Indians, who were always prowling around, "but" said one informant, "they will respect the English flag, and I advise you to take one along." Such a thing the party did not possess. But Mr. Bompas was equal to the occasion, so procuring some white and red cotton, he soon formed quite a respectable banner, which was fastened to a small flagstaff erected on the cart. Some distance out on the prairie mounted Indians appeared in sight, and, like the wind, one warrior swept down to view the small cavalcade. Beholding the flag of the clustered crosses, he gazed for a time upon the little band, and moving away, left them unmolested.

At length Red River was reached in safety, and from here Mr. Bompas took passage in one of the four boats of the Hudson's Bay Company, for the long journey north. For sixty-three days they pressed steadily forward, and reaching Portage la Loche on October 12th, they found that they were too late to meet any boat going farther north. But Mr. Bompas was not to be defeated. Engaging a canoe and two French half-breeds he pushed bravely on. The journey was a hard one and after almost incredible difficulties he arrived at Fort Simpson on Christmas Day. Here he was heartily welcomed by the Rev. W. W. Kirkby, who with great surprise upon his face, rushed forward and seized Mr. Bompas by the hand. It was a great meeting, and the hearts of both were cheered and strengthened.

Mr. Bompas at once learned that Mr. McDonald had recovered from his sickness, and was able to continue his work. Though this news filled him with thankfulness, yet he was disappointed for himself, as his heart had been set upon the Yukon region as his special field of work. He nevertheless began with much enthusiasm to learn the Indian language at Fort Simpson, assisted by Mr. Kirkby, with whom he remained until Easter, 1866.

Mr. Bompas then began those marvelous journeys over that vast country, which he continued for long years. He was ever moving from place to place, searching for the lost sheep in the wilderness, and preparing the way for those who followed him. His descriptions of these trips, the modes of travel, and the natives he met are -most interesting, and throw valuable light upon the country and its inhabitants.

A few years later we find Mr. Bompas among the Eskimos at the mouth of the Mackenzie River. He had travelled from Fort McPherson in company with two Eskimos, a man and boy, hauling a sled with blankets and provisions. On the way he received a message from the Chief of the Eskimos to defer his visit, as the Eskimos were starving and quarrelling, and one had just been stabbed and killed in a dispute about some tobacco. But this message had no effect upon the missionary; he was doing his Master's service and he knew that he would be guarded and guided.

For three days they continued to travel without any difficulty, camping at night on the river bank, and making a fire of broken boughs. But the glare of the spring sun was very severe, and Mr. Bompas was stricken with snow-blindness. For three days in awful darkness he was led by the hand of the native boy, making about twenty-five miles a day, until the first Eskimo camp was reached. It was only a snow-house, and to enter it with closed eyes, stumbling at every step, was a disagreeable introduction. And yet such sufferings were little considered by Mr. Bompas.

"They are delights," he once said, "The first footprint on earth made by our risen Saviour was the nail-mark of suffering, and for the spread of the Gospel I, too, am prepared to suffer."

After one day of rest in the snow-house, Mr. Bompas recovered his sight, and then, moving forward, reached another camp. The hardships he endured among these natives may be readily understood from a description in writing given to a friend in England.

"It would be easy for you to realize," he wrote, "and even experience the whole thing if so minded. First, go and sleep a night in the first gipsy camp you find along some roadside, and that is precisely like life with the Indians. From thence go to the nearest well-to-do farmer, and spencf the night in his pigsty (with the pigs of course) and this is exactly life with the Esquimaux. As this comprises the whole thing in a nutshell, I think I need give you no further description. The difficulty you would have in crawling or wriggling into the sty through the hole only large enough for a pig was exactly my case with the Esquimaux houses. As to the habits of your companions, the advantage would be probably on the side of the pigs, and the safety of the position decidedly so. As you will not believe in the truth of this little simile, how much less would you believe if I gave you all particulars? So I prefer silence to exposing myself to your incredulity, but if I had to visit them again I should liken it rather to taking lodgings in the den of a Polar bear, the first time in God's good providence he did not show his claws."

Harness yourself to a wheelbarrow or a garden roller, and then, having blindfolded yourself, you will be able to fancy me arriving, snow-blind and hauling my sledge, at the Esquimaux camp, which is a white beehive about six feet across, with a wav a little lareer than that for the bees.

"If you swallow a chimney-full of smoke, or take a few whiffs of the fumes of charcoal, you will know something of the Esquimaux mode of intoxicating themselves with tobacco, and a tan-vard will give vou some idea of the sweetness of their camps. Fat raw bacon, you will find tastes much like whale blubber, and lamp oil, sweetened somewhat, might pass for seal fat. Rats vou will doubtless find equallv good to eat at home as here, though without the musk flavour; but you must s?et some raw fish, a little rotten, to eniov a good Esquimaux dinner.

"Fold a laree black horse's tail on the top of your head, and another on each side of your face, and you will adopt exactly the Arctic lady's headgear. Then thrust a knife through the centre of each cheek, and leave the end of the knife-handle permanentlv in the hole, and you will experience the agreeable comfort of the Arctic cheek ornament. After this, get a dozen railway trucks, tackled together, and load them with large and small tow-boats,scaffold poles, a marquee, three or four dead oxen, the contents of a fish-monger's stall and of a small rag-shop, and then harness all your family, and draw the trucks on the rails from Alford to Boston, with a few dogs to help and thus you will have a very close resemblance to an Esquimaux family travelling in winter over the ice. As I have formed one of the haulers on such an expedition, I can speak from personal experience."

His great friend among the Eskimos was the old Chief Shipataitook by name, who had first invited him to visit them, and had offered the missionary the use of his camp, and entertained and fed him with the greatest kindness and cordiality. To the old chief, Mr. Bompas was indebted for his life not long after, and ever remembered him with the greatest affection.

When the ice had gone out of the Mackenzie River, the Eskimos began to move up stream to trade with the Hudson's Bay Company, at Fort McPherson, taking the missionary with them. It was a voyage of two hundred and fifty miles and much ice was encountered. For days they made slow progress and laboured hard. Then they became angry with one another, and also cast threatening glances upon the white man in their midst. They imagined that in some way he was the cause of all their trouble, and the angry glances were followed by threatening gestures, and Mr. Bompas realized that the situation was most critical. One night, after a day of unusually hard work, when little progress had been made, the natives became so hostile that Mr. Bompas feared they would take his life ere morning. But, notwithstanding the impending danger, the faithful servant committed himself to the Father's keeping, and, wearied out, soon fell asleep.

But old Shipataitook was to be reckoned with. He had taken a fancy to the brave young white man, and could not see him murdered without making an effort to save him. He had heard the threatening words, and when the plotters were about to fall upon the victim, he told them to wait, as he had something to tell them before they proceeded farther. Then he began a strange story, which, falling upon the ears of the naturally superstitious natives, had a great effect. He told them that he had a remarkable dream the night before. They had moved up the river, and were almost at Fort McPherson, and as they approached they saw the banks lined with the Hudson's Bay Company's men and Indians, all armed and ready to shoot them down in the boats if they did not have the white man with them.

When this story had been told, all plotting ceased and in the morning when Mr. Bompas awoke, he found no longer angry glances cast upon him, but the natives were attentive in their care.

On June 14th, the ice left them and the river became clear, so without more detention they continued on their way, "and arrived safely, by God's help," says Mr. Bompas, "at Peel's River Fort, on June 18th, about midnight."

Following his visit to the Eskimos, Mr. Bompas continued his wonderful journeys by canoe and dog team, and in 1873 we find him on the far-off Yukon River. On his way hither he visited La Pierre House, west of the Rocky Mountains, and the reception he met with from the Loucheux Indians there filled him with thankfulness, and encouraged him much in his work. Writing of these Indians, he says:

"I have been much cheered in my work among them, by finding them all eager for instruction and warm-hearted in their reception of the Missionary. Each day I spent in the Loucheux camps was like a Sunday, as the Indians were clustered around me from early morning till late at night, learning prayers, hymns, and scripture lessons as I was able to teach them. I never met with such earnest desires after God's word, nor have I passed so happy a time since I left England; indeed, I think I may say that, had I ever found at home such a warm attachment of the people to their minister, and so zealous a desire for instruction, I should not have been a missionary. These mountain Loucheux seem the 'fewest of all people' but I cannot help hoping they are a chosen race."

Mr. Bompas was much pleased with the Yukon River, and the beauty he saw on every side caused him to write:

"It is a splendid river with high wooded hills on each bank, occasionally broken into bold and cragged rocks. The margin of the river is rather flowery with lupins,,vetches, bluebells, and other wild flowers; and I was surprised to see a few ferns in the clefts of the rocks, so close to the Arctic circle. Gold has not been found in the Yukon, but I brought down with me some good specimens of iron ore, of which there seems to be a great quantity close to the river's bank. This may some day be utilized."

These words were penned during the summer of 1873, and what changes this missionary was to see before the close of the century! Instead of the iron ore which he thought "some day would be utilized," the gleaming gold would be luring thousands into the country.

But what a change was about to take place in the life of this noble man, for while he was quietly and humbly pursuing his work, a letter reached him, summoning him back to England, to be consecrated Bishop of the huge diocese. To the hardships and dangers of travel there was to be henceforth added "the care of all the churches."

While Mr. Bompas was performing his wonderful journeys in the far north, men no less earnest were following his movements and planning and praying for the success of the church in North-West Canada.

Owing to the statesmanlike plans of Bishop Machray, of Rupert's Land, it was decided to divide the vast district, comprising more than one half of all Canada, into separate dioceses. The Bishop realized that more effective supervision was needed in the large field, as the distances were too great for one man to think of undertaking. Crossing to England, the Bishop set forth the proposal for the division of his diocese into four parts, which was accepted by all concerned.

The reduced Diocese of Rupert's Land would comprise the new province of Manitoba and some adjacent districts; the coasts and environs of Hudson's Bay would be for the Diocese of Moosonee; the vast plains of Saskatchewan, stretching westward to the Rocky Mountains, the Diocese of Saskatchewan; and the whole of the enormous territories watered by the Athabasca and Mackenzie Rivers, and such part of the Yukon basin as was within British territory, the Diocese of Athabasca.

For Moosonee, the veteran missionary, John Horden had been consecrated Bishop, in 1872; and in the following year John McLean, and William Carpenter Bompas were summoned home to be consecrated Bishops of the new Dioceses of Saskatchewan and Athabasca.

Mr. Bompas shrank much from the thought of becoming a Bishop, and in July, 1873, he set his face homewards with the express purpose of turning the Church Missionary Society from the idea. It took him from July until New Year's Eve to travel from the Yukon to Red River, and the difficulties he encountered would have daunted a lesser man. It is said that when Mr. Bompas (in his rough travelling clothes) reached the episcopal residence and enquired for Bishop Machray, the servant mistook him for a tramp and told him that his master was very busy and could not be disturbed. So insistent was the stranger that the servant went to the Bishop's study and told him that a tramp was at the door determined to see him.

"He is hungry, no doubt," the Bishop replied; "take him into the kitchen and give him something to eat."

Mr. Bompas was accordingly ushered in, and was soon calmly enjoying a plateful of soup, at the same time urging that he might see the master of the house. Hearing the talking, and wondering who the insistent stranger could be, the Bishop appeared in the doorway, and great was his astonishment to see before him the travel-stained missionary.

"Bompas!" he cried, as he rushed forward, "is it you?"

We can realize how Mr. Bompas must have enjoyed this little scene, and the surprise of the good and noble Bishop of Rupert's Land.

Reaching England, Mr. Bompas was unsuccessful in dissuading the Church Missionary Society from carrying out their plan, so on May 3rd he and John Horden were elevated to the episcopate. The consecration took place in the parish church of St. Mary's, Lambeth, Dr. Tait, Archbishop of Canterbury, being assisted by Bishop Jackson, of London, Bishop Hughes of St. Asaph, and Bishop Anderson, late of Rupert's Land.

But Bishop Bompas was not to return alone to his great work, for a few days after his consecration, May 7th, he was united in marriage to Miss Charlotte Cox, by Bishop Anderson, assisted by the Rev. John Robbins, Vicar of St. Peter's, Netting Hill, and the Rev. Henry Gordon, Rector of Harting.

Mrs. Bompas was a woman of much refinement and devotion to the mission cause. Her father, Joseph Cox, M.D., of Montague Square, London, was ordered to Naples for his health. . During this trip, in which he was accompanied by his family, his daughter, afterwards Mrs. Bompas, acquired that love for the Italian language which ever after continued to be a great source of comfort to her. No matter where she went in the northern Canadian wilds she carried her Dante with her, which she studied with much delight in the original. Her interest in missions was aroused when the martyrdom of Bishop Patteson startled the Christian world, and she reached as she tells us, "the enthusiastic stage when we resolve to become missionaries ourselves, and are all impatient to be off anywhere--to China, Japan, or to the Indians of Mackenzie River."

Leaving England on May 12th, 1874, the Bishop and Mrs. Bompas started on their long journey, and after many trying experiences reached Fort Simpson, on September 24th. Their arrival caused much excitement in the place. The red flag of welcome was at once hoisted, and Mr. Hardisty, the chief officer of the Hudson's Bay Company and the whole settlement came to the shore to meet them. So hearty was the reception that they did not perceive the grim shadow of starvation that was hanging over the fort and land. There was only one week's provisions in the Company's store, and game was very scarce. At this point the new party arrived, bringing six extra mouths to be fed, besides the boat's crew, and yet the Company's officers received them with the utmost courtesy and good temper, and did their best to look and speak cheerfully. Most of the men around the fort had been sent away, and there was difficulty in collecting dried scraps of meat for the wives and children. At length there came a time when there was not another meal left. The poor dogs hung around the houses, "day by day growing thinner and thinner, their poor bones sticking through their skins. Even a dry biscuit could not be thrown to them." But just when matters reached the worst two Indians arrived, bringing fresh meat, and the great tension slackened.

"From that moment," says Mrs. Bompas, "the supplies have never failed. As surely as the provisions got low, so surely, too, would two or three sledges appear unexpectedly, bringing fresh supplies."

Little wonder that the Bishop acquired that great trust in Providence that caused him to say that "a restful trust in Heaven's bounty will lead to a cheerful content even in the far north, and make a man exult in the consciousness that his God is still present with him there."

Fort Simpson was chosen by the Bishop as his abode at first. It is situated at the confluence of the Mackenzie and Liard Rivers, and formed the most convenient point for managing the vast diocese. This position had been occupied years before by the Hudson's Bay Company, and here in 1859, Mr. Kirkby built the church and mission house.

All around stretched the huge diocese of one million square miles, and such a diocese! "To represent the length and tediousness of travel," the Bishop wrote, "it may be compared to a voyage in a row boat from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Fort William, on Lake Superior, or a European may compare it to a voyage in a canal barge from

England to Turkey. Both the length and breadth of this diocese equal the distance from London to Constantinople.

"If all the populations between London and Constantinople were to disappear, except a few bands of Indians or gipsies, and all the cities and towns were obliterated, except a few log huts on the sites of the capital cities--such is the solitary desolation of this land. Again, if all the diversity of landscape and variety of harvest field and meadow were exchanged for an unbroken line of willow and pine trees--such is the country."

And here once more the Bishop took up his work of forming Indian schools and visiting the natives. He was constantly on the move, and at times his life was in great danger from exposure to cold and flooded streams. Wherever he went the Indians came to him to be cured, bringing their sick and afflicted, and truly many an Apostolic scene was enacted there in the great northern wilds.

The Bishop loved the children, and a beautiful incident is that which shows us the missionary seeking little Jeannie de Nord, and carrying her home in his arms. He suffered greatly, but what did it matter? The lost one was found, and the Bishop's heart was happy.

Not only did the Bishop bring the Indian children into the mission school, but time and time again he and Mrs. Bompas received some poor little waif as their own. A few years after his consecration little Jenny, a mere babe, was thus taken to their hearts. She came to them, so Mrs. Bompas tells us:

"At holy Christmas-tide,

When winter o'er our northern home

Its lusty arms spread wide;

When snow-drifts gathered thick and deep,

Winds moaned in sad unrest,

My little Indian baby sought

A shelter at my breast."

Upon this child they bestowed their affection, but, alas! notwithstanding the greatest care, it gradually wasted away. It was a sad day to them both when the little one died.

Some time later another was received into their hearts and home. This was Owindia ("The Weeping One") who was baptized Lucy May. Several years later she was taken to England, where she died some time after. Mrs. Bompas beautifully tells the story of this waif in her little book, "Owindia."

As soon as possible after his consecration Bishop Bompas began to organize the forces at his command, and made preparations for the holding of a Synod. But his men were few and far removed, and months passed before word reached them at their distant posts. The difficulty, however, was overcome, and on September 4th, 1874, the first Synod of the vast diocese was held at Fort Simpson. Although small, it was an interesting assemblage which met on that early September day, unlike any other Synod ever before held. Foremost of the three clergy was the Venerable Archdeacon Robert McDonald, who had come from Fort McPherson, on Peel River. Next came the Rev. W. D. Reeve, afterwards Bishop of the Mackenzie River Diocese. The third was the Rev. Alfred Garrioch, recently ordained. Besides these there were Messrs. Alien Hardisty and William Norn, catechists, and George Sandison, a servant of the Hudson's Bay Company.

There were many things of considerable importance to consider at this meeting, and when the Synod ended the little band of workers had to hurry away to their distant posts, as winter was fast approaching. And away, too, went the Bishop. There were stations to visit which needed his attention, and he was delayed for some time. Upon his return he found Mrs. Bompas quite ill, which resulted in her return to England, with the opening of navigation.

During the year 1877, Bishop Bompas was called to Metlakahtla, to settle a dispute between William Duncan, in charge of the place, and Bishop Hills, of Columbia Diocese. It was a terrible journey he made up the Peace River, and over the mountains, with winter closing in upon him. But with almost superhuman effort he accomplished the undertaking, and reached Metlakahtla on November 24th. Although he received a hearty welcome from Mr. Duncan, he was unable to settle the difficulty, which continued, and forms a very sad chapter of the history of the Church on the Pacific coast. The following interesting account of the Bishop's visit has been furnished by the Venerable Archdeacon Collinson, of the Diocese of Caledonia:

"It was Mr. Morrison who met the Bishop, on his arrival at Port Essington. He was so travel-worn that Mr. Morrison mistook him for a miner as he disembarked from the canoe.

'Well,' said he, 'what success have you had?' The Bishop replied that he had been fairly successful, evidently relishing the joke. Just then Mr. Morrison saw the remains of his apron, and, recollecting that he had heard that a Bishop was expected at Metlakahtla from inland, exclaimed: 'Perhaps you are the Bishop who I heard was expected?' 'Yes,' replied the Bishop, 'I am all that is left of him!' He remained at Metlakahtla that winter, where he succeeded in confirming a large number of candidates. By the first steamer in spring he came over to me on Queen Charlotte's Island at Massett. I had a little bedroom specially prepared for him in the new mission-house, but he preferred lying down on the floor, as he said he was not accustomed to sleeping in rooms. He was about to lie down just across the doorway, when I begged him to take another position, as he might be disturbed by someone entering early or late.

"I returned with him to the mainland on the steamer. We went up together to the Naas River by canoe, a voyage of some fifty miles, to Kin-eolith. The owner of the canoe, who was a chief, was steering, seated forward. As the Bishop raised his arms in paddling, in which we were all engaged, it revealed a long tear in the side of his shirt. Suddenly the chief asked me in a low tone in Tsimshean, 'Why is the chief's shirt so torn?' I replied: 'He has been a long time in travelling through the forest.' He was dressed very roughly and wore a pair of moccasins."

Upon reaching his own Diocese, the Bishop found that a terrible famine had ravaged his flock during the previous winter.

"Horses were killed for food," he wrote, "and furs eaten at several of the posts. The Indians had to eat a good many of their beaver-skins. Imagine an English lady taking her supper off her muff. The gentleman here with me supported his family for a while on bear-skins. These you see at home mostly in the form of Grenadier caps. Can you fancy giving a little girl, a year or two old, a piece of Grenadier's cap, carefully singed, boiled and toasted, to eat?"

This severe "wasting of the famine" induced the bishop to launch the mission-farm plan which for some time he had had in mind. Peace River was chosen for the venture, which proved most successful, and was the beginning of the farming industries which have reached such large proportions.

In May, 1881, the Bishop began those marvelous trips which only a giant constitution could have endured. For long months he was absent from home, and upon his return the following winter he nearly lost his life, and was saved by an Indian sent by Mrs. Bompas to his relief from Fort Norran.

"After darkness had set in the following night," so Mrs. Bompas wrote, "the travellers appeared, trudging along on snow-shoes, weary and footsore, my husband looking hardly able to stand, and with his beard all fringed with icicles. It is wonderful how he had been preserved amid such perils, and brought to me at last, in answer to many prayers."

After almost twenty years of strenuous work in the north the Bishop desired a change. The incessant moving about was telling upon him, and he asked that the vast diocese might be divided. He maintained that the great extent of the country, three thousand miles long, rendered his supervision of the mission rather superficial, and he asked that an additional Bishop be provided for Peace River.

And this long-desired change at length took place, for while the Bishop was writing his letters by the camp-fires of the Indians, a definite step was taken by the Provincial Synod, and a new diocese was carved out of the old. This included the Peace River District, and retained the name of Athabasca.

Here, then, were two dioceses--one the Mackenzie River, stretching from the 60th parallel of north latitude to the Arctic Circle, and westward beyond the great mountains, bleak and desolate; the other, nearer civilization, and only half as large, but with great prospects before it. Which would the veteran take? The one which promised greater ease? No; that was never his way. Leaving Athabasca in charge of Bishop Young, who had been consecrated on October 18th, 1884, for the special field, he set his face steadfastly toward the frozen North, as far as possible from the restraints of civilization. Great was his satisfaction at the division thus made, for it would thus enable him to accomplish more definite work, and carry on his beloved translations.

But troublous times were ahead. First came the sad news of the death of one of his most earnest workers, Vincent C. Sim, who had been stationed at Rampart House on the Porcupine River. The year of Mr. Sim's death was the outbreak of the North-West Rebellion, which interfered with mission work, and the obtaining of supplies. This led to a famine throughout the land, and the suffering on all sides was great.

Notwithstanding all these troubles, the Bishop summoned his clergy to attend the first Synod of the Mackenzie River Diocese, in August, 1866. It was held at Fort Simpson, and so scarce was food that the members who attended were placed on short allowance. One day the dinner consisted of barley and a few potatoes. But the Bishop was equal to the occasion, justifying the scanty fare by quoting Proverbs xv. 17: "Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith."

The winter that followed the meeting of the clergy was a terrible one. The famine increased. Game was scarce; few moose were to be obtained; the rabbits all died, and fish nearly left the river. The Indians asserted that the scarcity of fish was caused by the propeller of the steamer Wrigley, which first churned the headwaters of the great river the preceding fall.

Space forbids a detailed account of the Bishop's travels, hardships and trials during the next few years. He became very weary of the vast field, and longed "to steal away to the Yukon," and he proposed Archdeacon Reeve to succeed him on the Mackenzie River. He had no inclination to leave the country, and when it was proposed that he should go to Manitoba he wrote: "I find the needle points west rather than east, and north rather than south." When urged to go to England, he said: "To life in England and to my relations there, I feel so long dead and buried that I cannot think that a short visit home, as if from the grave, would be of much use. If over fifteen years ago, when I was at home I felt like Samuel's ghost,--how would I feel now?"

Oh January 31st, 1890, we find him at Fort Norman, living in the church, with a large stove, and eating more flour, so he tells us, than he had done for twenty-five years. Truly his wants were few.

"An iron cup, plate, or knife," wrote the Rev. W. Spendlove, "with one or two kettles, form his culinary equipment. A hole in the snow, a corner of a boat, wigwam, or log hut, provided space, six feet by two feet for sleeping accommodation. Imagine him seated on a box in a twelve-foot room, without furniture, and there cooking, teaching, studying, early and late, always at work, never at ease, never known to take a holiday."

On August 5th, 1891, we find the Bishop still at Fort Norman, and in a letter to Mrs. Bompas, who was in England, he wrote:

"I am now engaged in packing up, with the view, if God will, of shortly and finally leaving Mackenzie River for the far west."

Meanwhile changes were taking place beyond the mountains, along the great Yukon. Gold had been discovered, and miners were flocking into that region. The missionaries there were much isolated, and there was need of episcopal oversight. The result was that in 1890, the Provincial Synod of the Province of Rupert's Land, sanctioned the division of the Diocese of Mackenzie River. Archdeacon Reeve became Bishop of the eastern portion, while Bishop Bompas gave himself up to the work along the Yukon River.

Even after the division was made the Bishop had no small sphere of work before him. His new diocese comprised 200,000 square miles-- more than twice the area of Great Britain, and the third largest diocese in British America. It stretched from the Diocese of Caledonia, on the south, to the Arctic Ocean on the north, and was separated on the west by the 141st meridian longitude from the United States territory of Alaska. To this new diocese the bishop gave the name of "Selkirk."

The Bishop made Forty Mile his headquarters. This was at first an Indian village, on the Yukon River, but it soon became a central place for miners. The latter exerted a baneful influence upon the natives, demoralizing them through drink, and in many other unlawful ways. But notwithstanding these drawbacks, work went on apace. The Indian School made fair progress, and steadily the natives were brought into the fold.

For the Bishop and Mrs. Bompas, the miners had nothing but the profoundest respect. Though many of them were indifferent to all things spiritual, still they could admire nobleness when they beheld it, as they did every day in the two faithful soldiers of the Cross in their midst. As a token of their esteem, on Christmas Day, 1892, a splendid nugget of gold was presented to Mrs. Bompas, with an address signed by fifty-three miners.

Each spring was a season of anxiety to the Bishop and his household. The mission-house was on an island, and when the ice of the great Yukon was going out there was often much danger. As the mighty block of ice moved by, and then jammed and piled high, the water would rise and flood the buildings. Several times they were awakened in the night to find the water rushing through the house, and were forced to climb aloft until the waters subsided.

While the Bishop was carrying on his steady work at Forty Mile, an event of world-wide importance was taking place farther up the river. Gold had been discovered on the Klondike, in July, 1896, and the following year a rush of humanity took place, which has scarcely a parallel in history. The City of Dawson sprang up like magic into existence, and in a few months the Bishop found the world of civilization thrust upon him. Prices soared to an alarming degree, and people went almost crazy over the golden lure.

This new responsibility was a severe trial to the Bishop. So long had he laboured among the Indians, that, as he sadly acknowledged, he was entirely unfitted for work among the whites. This he entrusted to others, especially to the Rev. R. J. Bowen, who at once started up the river to plant the Standard of the Lord in the excited camp of gold-seekers. He was wonderfully successful, erected a church, and won the respect and goodwill of all.

In 1901 the Bishop and Mrs. Bompas bade farewell to all at Forty Mile, and started for Caribou Crossing, a small village in the southern portion of his diocese. The accommodation at this place was most meagre. A tent, which belonged to Bishop Ridley, gave them shelter for a few hours, when, hearing of a bunk-house across the river, they at once rented it, and afterwards purchased it for one hundred and fifty dollars. It was dirty and uncomfortable, but the Bishop placed a rug and a blanket on the big table for Mrs. Bompas to rest on, while he went to explore. The house was infested with gophers, which ran along the rafters, causing great annoyance. But notwithstanding the toil of the day, evening prayer was held in Bishop Ridley's tent. Here the services were conducted until the fall, when the weather grew so cold that Mrs. Bompas' fingers became numb as she played at the little harmonium, which she had brought with her.

After that, services, morning and evening, were held at the mission-house, "which," as Mrs. Bompas tells us, "had been used as a road-house, and post-office, and possessed one good-sized room, over the door of which there still exists the ominous word 'bar-room' (now hidden behind a picture) ; and in this room, we had to gather, Indians and white people, for Sunday and week-day services, baptisms, marriages and funerals, for school-children and adult classes, etc."

Anxious days followed the Bishop's removal to this place. Clergy were scarce in the diocese, when Mr. Bowen left Whitehorse earnest appeals were sent "outside" for men. Then it was, upon the Bishop's earnest request, that the Rev. I. O. Stringer arrived, in November, 1903, to take up the work laid down by Mr. Bowen. Much pleased was the Bishop to have Mr. Stringer so near and at once marked him as his successor.

Then followed the death of his old friend, Archbishop Machray, and as senior Bishop of the Province of Rupert's Land, Bishop Bompas was summoned to Winnipeg. Though he shrank much from the thought of leaving the north to mingle with the bustling world, yet after a few minutes' thought, he sent back the following answer: "I will try to be with you by Easter."

The Bishop's time was fully occupied during his stay in Winnipeg. There were old friends calling upon him, reporters seeking interviews, meetings to attend, and addresses to deliver, which wearied him a great deal. The Archbishop of Rupert's Land, in an address at the 107th anniversary of the Church Missionary Society, at Exeter Hall, London, April, 1907, thus referred to Bishop Bompas' visit to Winnipeg:

"Dr. Bompas, that splendid veteran missionary, who came down at the time of my election :--he was as humble as a little child--when he stood on the platform of a great missionary meeting and when I, introducing him, spoke of the hardships he had gone through, corrected me thus when he started to speak. He said 'It is you men at the centre, with your telephones and your telegrams, who have the hardships. We have a soft time in the north. Nobody worries us.' That is all he said about his hardships. Then he told the story of his work in a simple, childlike way."

But the city life did not agree with the Bishop, and he was not happy until he had returned to the quietness of his little log cabin at Caribou Crossing. The work here was all that he desired. To care for the school, to minister to his dusky flock, and to carry on his beloved translational studies, occupied his time. He longed to be relieved of the care of the diocese, and great was his pleasure when at length a message arrived summoning Mr. Stringer to Winnipeg for consecration. Anxiously he awaited his successor's return, and when he at last arrived, he handed over the affairs of the diocese, and at once prepared for his journey to Moosehide, an Indian village just below Dawson, where he intended to spend the remainder of his life as a humble missionary. Let Mrs. Bompas tell the story of the final scene in the life of that devoted man.

"A passage for the Bishop and Mrs. Bompas and two Indian girls had been secured on one of the river steamers to sail on Monday. This was Saturday, June 9th, a day calm and bright, as our summer days in the north mostly are. The Bishop was as active as ever on that day. Twice he walked across the long railway bridge, and his elastic step had been commented on as that of a young man. Later he had been up to the school, and on to the Indian camp to visit some sick Indians. Then he went home, and remained for some time in conversation with Bishop Stringer, into whose hands he had already committed all the affairs of the diocese. Then the mission party dined together, and at eight o'clock they all assembled for prayers. After prayers the Bishop retired to his study and shut the door.

"Was there, we wonder, any intimation of the coming rest, in the breast of that stalwart warrior, whose end of life was now so near as to be reckoned not by hours, but by minutes only? We know not. Sitting on a box, as was his custom, he began the sermon which proved to be his last. Presently the pen stopped; the hand that so often guided it was to do so no more. Near him was one of his flock, an Indian girl, who needed some attention, and as he rose he leaned his elbow on a pile of boxes. And while standing there the great call came; the hand of God touched him, and the body which had endured so much fell forward. When Bishop Stringer reached his side a few minutes later, the Indian girl was holding his head in her lap. Nothing could be done, and without a struggle, without one word of farewell, the brave soul passed forth to a higher life.

"There is a humble grave in one of the loveliest and most secluded spots in the Yukon Territory. Dark pine forests guard that grave. During the winter months pure untrodden snow covers it. It is enclosed by a rough fence made of fir-wood, which an Indian woodman cut down and trimmed, leaving the bark on, and then fixed strong and stable around the grave. But none will disturb that spot; no foot of man or beast will dishonour it; the sweet notes of the Canadian robin and the merry chirp of the snow-bird are almost the only sounds which break the silence of that sacred place. The Indians love that grave; the mission children visit it at times with soft steps and hushed voices to lay some cross of wild flowers or evergreens upon it. There is a grey granite headstone with the words 'In the peace of Christ' and the name of him who rests beneath. It is the grave of Bishop Bompas."

In a sketch like this it is impossible to do more than refer to the Bishop's literary work and to say that it was very extensive. After his death there was found an old wooden box containing a mass of interesting manuscripts. Some day a worthy and loving thought into the past, a little gift of material and bring it forth for the benefit of mankind. In the meantime the best that those old papers can do for us "is to bid us cast a wistful and loving thought into the past, a little gift of love for the old labourer who wrote so diligently in the forgotten hours, till the weary, failing hand laid down the familiar pen, and soon lay silent in the dust."