It is a melancholy reflection that the men who sought most

devotedly and enthusiastically to restore our English churches

to their pristine glory were the very men, in the end, who completed

the destruction of their character and beauty. About the middle

of the nineteenth century there arose the ecclesiological movement,

following on the work of Pugin, which set itself to the great

ideal of making our churches the glorious centres of worship

they once had been. A famous pamphlet was issued, called Reformation

and Deformation, which gave telling pictures of what churches

had been like in the Middle Ages, and on the opposite page illustrations

of what they were like in the early Victorian era. Now those

slovely Victorian churches were neglected and overlaid, but they

were in great measure intact; if a few things--the high pews

especially--had been carefully removed, and the services carefully

improved without breaking with tradition, the old beauty would

have come back, and the people would not have become estranged

from their parish churches. This, alas, did not happen. Wholesale

destruction, under the guise of 'restoration,' began; and the

churches were filled with horrible travesties of mediaeval furniture.

They lost their home-like character. Worst of all, the central

feature of the church, the altar with its reredos, was distorted

out of all knowledge.

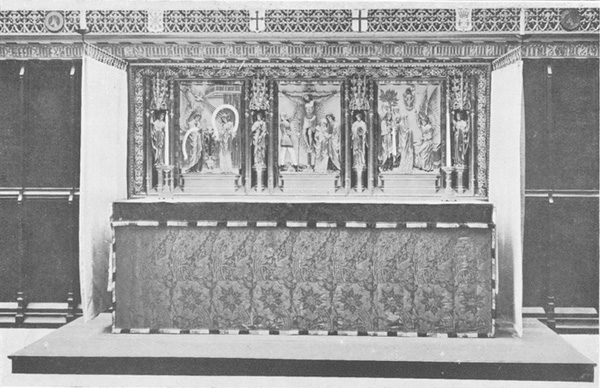

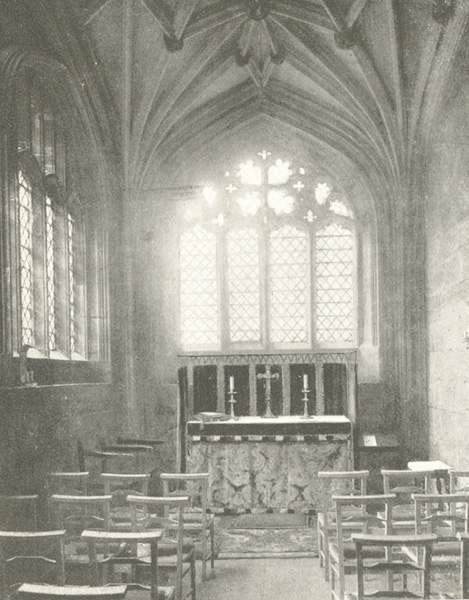

Few old churches escaped the new 'deformation,' so well-meant,

and so disastrous in its results. Chelsea Old Church and a score

or so of other churches in remote villages remain to show how

lovely and home-like our churches used to be. The altar in the

chancel was almost invariably spoilt. This is why the improvement

of altars is at the present time still mainly in the side-chapels,

which are generally not encumbered with bad reredoses. Every

one who travels about England must have noticed how, in one village

after another, the 'English altar' has reappeared, first in a

side chapel, and then, as people saw its points, in the chancel

as well. The process of recovery has begun in side chapels and

in new churches, as our illustrations show; but one by one high

altars also are now being modified or reconstructed.

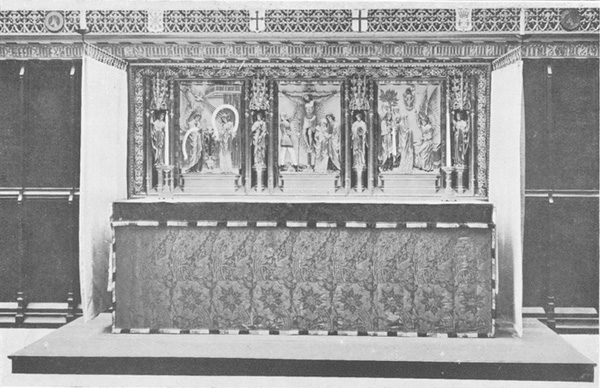

People call these altars 'English altars,' because they must

have some name; but they are really Catholic altars--the type

which, in more than one form, persisted from early times over

the whole Church, and only succumbed, two centuries after the

Renaissance had begun, to the Baroque influence of the counter-Reformation.

There are many Flemish pictures in the National Gallery to show

this; and all over Italy from Giotto to Ghirlandaio and the painters

of the sixteenth century, the pictures show no other form of

altar.

The same is true even of fifteenth and sixteen century Spain

(where the sunlight was excluded by the retablo); and the miniatures

of France and Germany tell the same story as those of England.

What that story is our illustrations show.

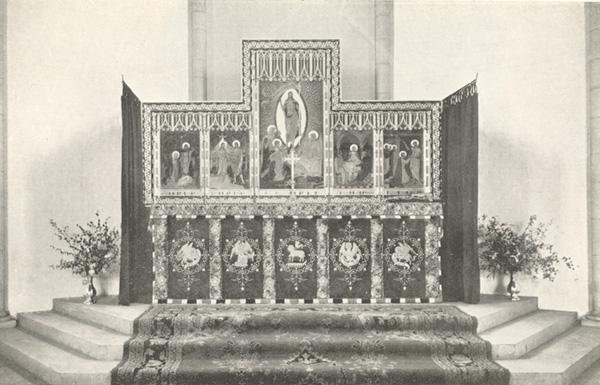

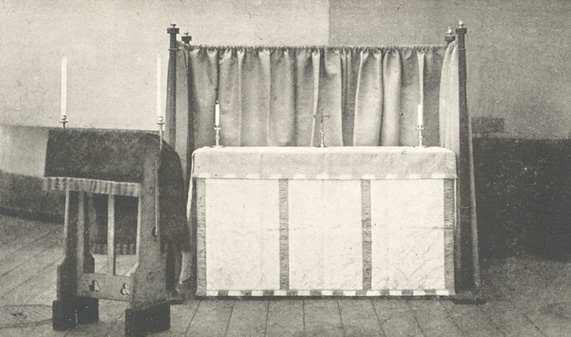

It will be noticed how extremely convenient this Catholic

altar is for mission chapels, and for places (as on board ship)

where an altar is temporarily set up. The whole place at once

becomes church-like in the best sense. But it is equally admirable

in a great cathedral, as the high altar of Westminster Abbey

shows. It is also forced upon us (unless we do violence to all

architectural principles) by our old parish churches, just because

they were built for it, and their low east window requires a

reredos not more than about three feet high. Our illustrations

show how dignity is secured more surely in this way than in any

other.

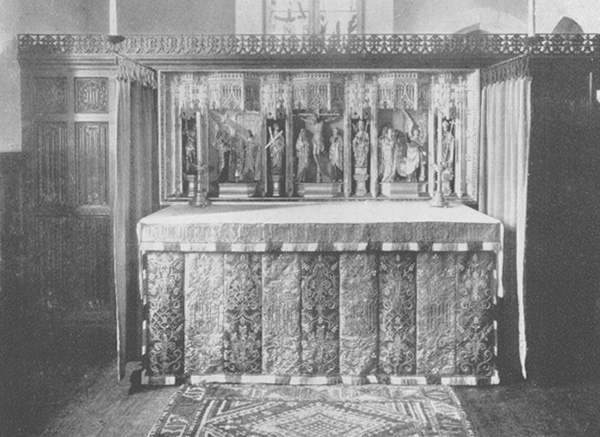

Just as I am writing this, the last volume of Michel's great

Histoire de l'Art has arrived from Paris, and I notice

that among much condemnation of modern church architecture, an

exception is made for Mr. Comper, and for Mr. Howard, who is

honoured by a special illustration, and who has designed so many

of our Warham Guild altars and screens. [The screen by Wigan

illustrated in Michel's Histoire de l'Art was executed

by the Warham Guild.] Last year an interesting sign came from

another quarter; there is an ecclesiological Society in Spain

which has issued from Barcelona in its Anuari for 1925 a picture

of a frontal with 'Warham Guild' underneath it.

Indeed there is a general agreement nowadays among architects,

artists and ecclesiologists. Not in one restricted model (for

riddel-posts are not of course necessary, beautiful as they are--and

even riddels can be dispensed with--and altar-crosses also),

but in the general principle, the type of altar illustrated in

these pages is now agreed to be, with the ciborium type of basilican

churches, that required by our architecture, and by the traditions

and requirements of Catholic worship.