I was brought home from Malta when quite a small child, and

I well remember a lady calling to see my mother, and saying just

before leaving, "I am going to a Missionary Meeting this

evening; would you like me to take your little girl?" I

asked, "What is a Missionary Meeting?" On being told,

I much wished to go, and was allowed to do so. It was a meeting

for the mission in Tierra del Fuégo.

I could not very well understand what the Deputation was saying,

but at the close the Chairman spoke very simply; one thing he

said being, that the youngest child present could do [3/4] something,

and he suggested various ways. I remember looking around and

thinking that I was one of the youngest present, and how much

I should like to do something. When I got home I asked my mother

if I might be a collector. She thought I was too young to understand

what it meant, but I pleaded to be allowed to try to get some

money for the mission, and at last she said I might.

A very young Collector grows into a Missionary.

Often she went with me. I had no missionary box, nor even

a collecting card, but only a piece of paper and a pencil, and

I often wonder that people gave me any money at all. We simply

went from door to door. Some people were very kind; I remember

how delighted I was one day, when two ladies asked me in and

each gave me half-a-crown, saying, "You are a good little

girl and you may come to us again next year."

The first year I think I got 15s. and wrapped it in paper

and put it into the collection at the meeting. This I did for

many years, and I remember how very pleased I used to be when

the time for the annual meeting came round, and how often I felt

the desire to be a missionary some day, and asked God to make

me one. In after years He answered my prayers, and I was privileged

to go and work among the very people in whom from the first I

had been interested.

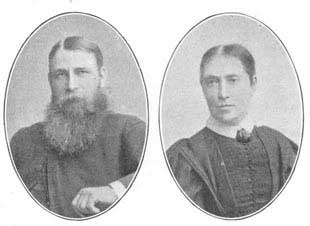

Mr. L. H. Burleigh at Keppel.

My dear husband also loved the heathen, and for many years

he also had had a longing desire to go [4/5] to the Mission field,

and was waiting for his way to be made plain. In 1878 he offered

to go to Keppel Island, one of the West Falkland Group, and was

accepted, and left the same year. I followed in August, 1879.

It was very happy work teaching the lads who were brought

from Tierra del Fuégo in the Allen Gardiner. The

first thing to do was to learn the language. My husband had two

lads in the house with him who were most helpful to him in learning

the language, so that when I came he was able to help me much.

Each day opened with prayer in the little Service room, then

School morning and afternoon.

Some of the boys were very intelligent, and fond of asking

questions; others were very dull and forgetful. Twice a week

we had a sewing class for the boys, to teach them to mend their

clothes, and they always looked forward to these afternoons with

great pleasure. Some learnt to patch and mend quite nicely. We

had a practice on Friday Evenings, and often twice a week; they

were very fond of singing and kept very good time. On the other

evenings in winter we let them play games; they were very fond

of snap, and we used to save up cardboard and cut it up and let

the boys draw and paint a flower or a ship or anything they liked,

so making their own game. We found them rather clever at drawing.

Occasionally we showed them the magic lantern, which they much

enjoyed, asking many questions, often very sensible ones. We

were able to teach them a great many useful things from the slides.

[6] On Saturday evenings we had a Prayer Meeting in our house,

a time that we all looked forward to, and I can testify to many

blessed results. I think the lads were very happy, and appreciated

all that was done for them. There were some who gave us much

trouble and anxiety, but on the whole we felt much cheered in

our work. They were also taught farming by a good Christian man

who had been on the island for many years, and who took the greatest

pains to try to make them useful men, so that when they returned

to their country they might teach their poorer brethren.

The Cape Horn Islands.

Though we were very happy at Keppel, we always had a longing

to be in the country of the people. I so wanted to be amongst

the women and children, One Saturday half-holiday a native came

to borrow something, and after I had given it him, he said, "Please,

mam, I like talk to you about my country people." I encouraged

him to tell me about them. He seemed very anxious about some

of his distant relations, who were living on the islands round

Cape Horn. He said, "You know, mam, my poor people down

there are not like we are here. Here we are clothed and fed and

taught to work, and you tell us the good news about Jesus, and

we are made happy; but down there my poor country people are

very unhappy, and sometimes white people (he meant the traders)

go there and treat them very cruelly."

[7] He told me a great deal that made me very sad, and I said,

"How would it be, Jack, if we went down there?" He

seamed very glad, at the same time rather apprehensive lest some

might hurt us, as no missionaries had ever lived among them.

When my husband came home I told him of this interesting conversation,

and it kindled in both of us a longing desire to go to those

"sheep without a shepherd," on those desolate islands.

When our dear Bishop Stirling visited our station a short

time after this, we told him how much we should like to go and

work among the Wollaston Islanders. There were hindrances, and

we asked God to make the way clear. Funds were low, and the Committee

did not feel justified in opening another station further south

than Ushuaia. We just left the matter in God's hands, knowing

that He would make the way plain if it were His will that we

should go. By and by we did go.

We did not ask for a house, because we knew how very expensive

building materials would be, but there was a little hut on the

sheep island off Keppel that was used for housing some of the

wool; this could be spared, and we told our Bishop that we should

be quite contented to have that for our home until we could get

a house, And very many happy days have we spent in that little

hut. We soon got our few things together, and found ourselves

sailing in the Allen Gardiner to our new home.

Wollaston Station.

After a stormy passage, and a short unavoidable delay at Ushuaia,

we anchored between two [7/8] islands. [The Mission Station is

marked on the Admiralty chart of Tierra del Fuégo, between

Grevy Island and Bayly Island, in the North-West of the Wollaston

Group. It was opened in 1888, the island on which it was situated

being ceded to the Society's Agent for that purpose. In 1892

the station was removed to Tekenika, with the view of obtaining

a better climate.] We went prepared to find the people in a very

miserable condition, but I can never forget the look of the poor

wretched creatures; it was indeed hard to believe that they were

human. A sadder sight even than this awaited us.

Some few days after, when the Allen Gardiner had left

us, about ninety-five most wretched looking objects came up from

the Horn. The two chief medicine men with this party were not

liked, so they came up rather cautiously--all the canoes and

people being left at the back of the island--to see if they would

be received in a friendly way. After two or three skirmishes

and orations from both sides, they decided that the party might

come up, and in due time they came.

The Natives.

I never saw such a sad and sickening sight. Some poor things

were ill, others looked so wicked. They surrounded us, and some

of the men began to crowd round my husband. They were all painted,

and the old witch-doctors looked ghastly, with their head-dresses,

spears, bows and arrows. The people had no clothes, only a skin

worn on the shoulder, and they were all in a most filthy condition.

They examined my husband first, and [8/10] then came to me, and

many amusing remarks were passed.

We both felt saddened, but we thanked God for allowing us

to be the privileged ones to go to these poor creatures, and

we asked Him to incline their hearts to receive us kindly. We

told them that we were their friends, and that we had come to

live amongst them and that we had good news for them; and we

asked if they would be willing to help us. Really they worked

very well. Each day opened and closed with prayer. We had no

service room, so we tied our bell to one of the trees, and the

people used to assemble there. The trees around the Horn are

nearly all crooked, bent by the prevailing winds; but it was

a great treat to see even these, after living in the Falkland

Islands, where there are none.

In due time we got up a shed; the sides were banked up with

turf, and the roof was of thatch. It was very cold and damp,

but better than being in the open air in such a terrible climate.

Teaching them Cleanliness.

When I saw the wretched state of the women and children I

longed to begin with them, but it was most difficult to know

what was best to do first. My dear husband and I talked it over

prayerfully, and we came to the conclusion that we had better

try to teach them habits of cleanliness. This I think was the

hardest work of all. For the first twelve months I used to wear

a loose cotton garment that I could often change, or I could

not have gone amongst them as I did. From the first I let [10/11]

them see that I was not afraid of them; I used to go in and out

of their hovels freely, wanting them to feel that I was their

friend, and encouraging the women to come to me with their troubles,

of which they had many.

Head Washing.

Most of the women were very sad-looking creatures; their heads

were like mops, the hair matted, and in a most disgustingly filthy

condition. However they listened to advice and we soon got this

remedied. Indeed from one extreme they passed to the other; sometimes

they would wash their heads many times a day, and often when

I was in a hurry and wanted a certain woman's help and could

not see her, someone would say, "She is washing her head."

They were very anxious to know if they should get their hair

to look like mine y I told them that if they did as I wished,

I thought they might. This pleased them greatly. They think fair

hair very lovely. Of course I told them I was not clever enough

to change the colour. The difficulty at first was how to get

brushes and combs; I had quite forgotten about this, but in due

time some kind friend in England sent us a large bag full of

all sorts and sizes of brushes and combs; there were great rejoicings

when these arrived, and I was rewarded by seeing what pains the

women and children took to keep their hair neat and clean,

A Mothers' Meeting.

After this I was able to teach them to work. Some of the women

turned out to be really clever [11/13] at needlework, and many

were the garments they were able to make. When we got a shed

put up I used to have a meeting for the mothers every week. Two

or three of the women would come to my hut, and I used to lend

my table, the only one on the island. I wanted something to keep

the work in, and I asked six of the women between them to make

three large Fuégian baskets, which they very willingly

did. [These are made of a very strong and tough rush that grows

freely in swampy places on these islands.] They had no forms

to sit on, so the men got us some posts, and my husband had them

put in the ground and planks nailed on them.

The mothers used to bring their babies, and four big girls

from the Home used to take care of them. The few toys that my

own little girl had were in great requisition. I always opened

with a hymn and prayer and scripture, and during the afternoon

I had many opportunities of nice talks with the women. In this

way I got to know their troubles and all about them, and was

often able to help my dear husband in solving little difficulties

that would arise with the men. I felt very happy in my work.

The Day's Routine.

At 8.45 the bell rang for prayers, and as a rule all on the

island attended, except those who were sick. After prayers, the

women worked for the mission. Owing to the wetness of the climate

the ground on these islands is in most [12/13] parts very swampy,

and it was necessary to make roads round the mission station,

the women liked to work at this, and they were much the better

for being employed; it kept them from thinking of the past and

from grieving, and they were always much happier when they were

busy. When the weather was fine, they would go in their canoes

fishing, but when they worked for the mission they were paid

in food.

The Climate.

The climate around Cape Horn is terrible; we averaged 300

wet days in the year, rain and snow, and 25 gales of no ordinary

character. It is a fearful coast, and humanly speaking not fit

for habitation. Since I have been in England I have often been

asked, "How could you live at such a post, and among such

wretched people?" My answer has always been that God's command

must be obeyed, and one of our Lord's last commands was, "Go

ye into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature."

That means that those dear people on those islands had to be

reached; some one had to go and do the work there, and we were

the privileged ones.

God gave us wonderful health. Often when these gales were

raging we had to hang blankets and cloths round the walls of

our hut to enable us to keep a fire and to burn a candle. In

consequence of the swampiness of the soil nothing would grow,

and while we were so far south we had no vegetables of our own.

Whenever an opportunity offered, our kind friends at Ushuaia

and Down-East [13/15] always sent us some of theirs, also the

Allen Gardiner when able would bring us some from Keppel

Island.

Nothing was wasted at the Mission Station. When the people

found that we had potatoes, they would come and beg for the parings,

and would boil them and think them a great treat; our tea leaves

also were much sought after. While the storms were raging the

people could not get any fish, and then they would wander about

the camp to gather roots, berries, and fungus.

A Stranded Whale.

Very rarely a whale would be stranded on one of the neighbouring

islands, and then there would be great rejoicings. All the people

would nock to that part, and would very soon begin to look better.

They thrive on whale flesh, and it is perfectly astonishing how

much they can consume at a time. On these occasions I would go

into the wigwams, and see huge pieces of whale roasting before

the fire, and on asking whose this piece was, some man or woman

would reply, "That is mine, for me to eat," and he

or she would soon get through this large joint.

The oil is much liked. I have often seen great junks of blubber

before the fire, with a tin or a shell underneath to catch the

oil; and little children and grown-up people dipping berries

into it and eating them as a relish. We taught the people to

mix their flour into dough, and instead of roasting the cakes

on hot stones before the fire, to fry them in some of the oil;

and how they liked them! The [15/16] little babies also were

very fond of sucking a piece of blubber.

The Clothes Line.

In the afternoons the women came to me, and I used to teach

them how to do useful things. It was always my custom on Monday

mornings to brush our clothes before putting them away, and if

the weather allowed, I always hung them up for a short time on

a clothes line. Some of the women used to help me, and one day

several of them came to my hut and asked me to give them a clothes

line. I said that I had only my own, and it was very rotten and

knotted; and I asked what they would do with it if I lent them

mine. They said, "We should hang out our things and brush

them as you do yours." I was much amused, because in those

days many of the poor things had only one garment. Later in the

day they came to say that they would not trouble me to lend them

mine, as they were going to make some with the sinews of the

whale, in the same way as they made their fishlines. This was

a capital idea, and I was glad for them to make one for my use

also. They asked me for a clothes brush, and I gave them one

that had done good service. I thought it would teach them, when

they had more clothes, to keep them wholesome. After this, on

the Monday the clothes would be hung out; it was most funny.

A Clever Needlewoman.

These people are very imitative. One day a woman came to ask

me to give her a little jacket [16/17] for her boy. She was a

very deserving woman, and I was sorry not to have one for her,

but I gave her a little body without sleeves, and promised to

cut out for her a jacket to make for her boy. She took it home,

and about an hour afterwards I heard a little voice calling me.

It was this boy, telling me to look at him: he had the jacket-body

on, and one sleeve, and he was saying that "one of his arms

was cold and the other warm." I found that his mother had

cut out and made a sleeve from an old piece of brown rag. Telling

him to say to his mother how pleased I was, I gave him a piece

of serge for her to make a sleeve for his other arm. Next morning

he was calling to me to come out and look at him; holding up

two arms, he told me they were both warm. One was in brown rag

and the other in serge.

I sent for the mother and told her how pleased I was that

she had made the sleeves alone, and asked her to bring up her

old jacket that she wore in her canoe. As the women generally

do all the paddling, the under part of the sleeves wears out

very quickly. Up to this time I had always cut out the sleeves

for them, and was hoping soon to teach them; but I thought that

as she had put sleeves into the child's jacket she should try

to do her own also. I told her I felt sure she could do it, and

I let her see that I could trust her. The next day she brought

the jacket to me, nicely done, with the seams in the right place.

I was delighted, because now she would be able to help me in

teaching the others.

[18] Without Natural Affection.

In the early days some of the women were very unkind to their

children. I have known some whose babies were ill, and if the

day happened to be calm, they have done away with the sick child,

and gone off in their canoes to fish. Others have brought them

and put them inside the door of the Home, and have gone away

for two or three days together.

One case I well remember. My husband had gone to another island,

and I was alone with the people. This woman wanted to go fishing,

and she brought her dying boy to me and said, "I am going

fishing, and I have brought my child to you." I felt that

if refused, she would be very cross, and perhaps hurt the child;

so I took it in and nursed it for three days, when it died. She

stayed away; for five days. Had my husband been at home I should

have acted differently,

That woman afterwards became a Christian, and as the light

dawned upon her soul, love for her other child came also. She

took great care of him, and he grew to be a very nice boy. We

greatly hoped that one day he would be a teacher to his people;

but God willed it otherwise, and he was accidentally burned to

death. This was a severe trial to the poor woman. She herself

in after years was drowned.

Another woman, a very bad character, was trying gradually

to starve her child; and she was so sly about it, that only at

the last did we find her out. She really had been decoyed away

by the [18/19] miners, and she wanted to be rid of her child

and be off. The dear little fellow was very sickly, and one night

between 12 and 1 o'clock she managed to put an end to his existence.

My husband had seen him just before midnight, and had given him

a few spoonfuls of beef tea. Half an hour after, a man came to

tell us that the child was dead, and that the mother had taken

it to a certain place to cover it over, and was going in her

canoe to join a party some way off. He also said that after my

husband had left, she had put the child out in the snow, It was

very courageous of this man to tell us for in those days they

were dreadfully afraid of one another.

My husband knew the direction in which she had gone, and went

to meet her. She thought we were asleep, and had taken two little

girls, one of them her own, to help her, hoping to get away unobserved.

She had her canoe quite ready, and two other wicked women were

in league with her. Presently my husband saw her coming in the

direction of her canoe, and he went up to her. She said as it

was such a fine night, she had been for a walk. "What!"

said my husband, "leave your baby ill, and go for a walk?"

She said, "I left him sleeping nicely." My husband

looked at her and said, "I know what you have done; don't

try to deceive me; I have had your canoe removed, and you are

not going away. I insist on your going and bringing me the body

of your child." He was a fearless and most determined man,

and one needed to be such in dealing with these people. In about

an hour we saw her coming [19/20] with the little emaciated body.

My husband rang the station bell, and ordered all the community

to assemble; for three-quarters of an hour he spoke very plainly

to them, and from that time we never had a similar occurrence

at the station.

Whilst my husband was speaking to the people I went and hunted

for the woman's little girl. She was about nine years old, and

very small and stunted. After a long while I found her hidden

under some filthy rubbish in a wigwam ready to be carried away

in a canoe. She had often asked me to ask her mother to let her

come into the Home, but the woman found her useful in the canoe

to bale out the water. I brought her away, and she was in the

Home till her death, about the year 1897. When first we had her

she was a miserable object, and for some months a great sufferer

through neglect; but she grew stronger, and improved greatly.

She was a good girl, and did what she was told, and was very

happy in the Home, but I cannot say that she was a decided Christian.

I told the mother that I had taken her little girl away from

her, and that when we saw she was a different woman, and able

to take care of her child, she might have her if she wished;

and she could come and see her in the Home twice a week. As a

punishment for her misdeed she was not employed by the Mission

for three months, and she was deprived of all privileges. I talked

to her and advised her to mend her ways, and promised that I

would help her. However, she was not penitent, and would go away

with the miners. Three months after she died.

[21] A Brighter Side.

I was greatly cheered by many of the women; they began to

take some pride in themselves and their homes, and to keep their

children clean and tidy.

On one occasion the boat had gone to Ushuaia to get provisions,

and met with very stormy weather on the return journey. One night

they managed to land, build a wigwam, and stay there for the

night; as they were tired, they threw themselves on the ground

by the fie, and one of the men's coat sleeves got burnt. The

next day the boat reached us, and this man came up with his coat

asking if I would give him some material for new sleeves. I remembered

that some kind friend in England had sent in a parcel of clothing

two black cloth sleeves, so I gave them to him and showed him

how to put them in. He was very pleased, and went home; next

day he came to show me his coat, and I praised him for having

put in the sleeves so well. He looked at me and said, "I

not do it, mam." I asked, "Who did then?" Very

proudly he replied, "My wife," adding, "When your

husband's things want mending you do them, and when mine do,

my wife does them."

Pleased as I was, I was made to feel how responsible was my

position, I was being constantly watched and copied, and I had

need continually to wait upon God and ask His guidance every

day, even every hour.

[22] An English Baby.

Some time after this a little son was sent to us. The people

were delighted; many, having never been off the islands, had

never seen an English baby, and there were great rejoicings.

Many were the kindnesses I received at that time from these dear

people. I felt that now I should indeed be able to help them,

and I hoped that they would copy me in this also, which they

soon began to do.

I used to allow some of the clean mothers to come and see

me bath my baby, and they simply wondered at everything they

saw. I remembered that some kind friend had sent me a cake of

Pears' soap, and I used to wash my baby with this. These people

noticed that I used red soap, but they used white^ and they asked

what it meant. I told them, and they immediately said, "We

should like some to wash our babies with." I cut my cake

into four, and gave each woman a piece, on the promise that they

would use it only for their babies, and they kept their word.

Next they wanted a tub. I had only one to spare, and it leaked

a little, but I thought it would not matter, as their floors

are of earth; so they had the tub, and really, after a while

they began to keep their babies so clean that one could nurse

and kiss them. When the sun shone I took my baby out and walked

up and down with him, and they would do the same with theirs,

saying, "Now we are like English women." All this gave

me splendid opportunities of talking to them, and they would

listen and be so pleased.

[23] The Medicine Men.

We were greatly hindered by the medicine men and their party,

of whom there were many when first we went. It was painful to

see what influence they had over the people, and how everything

they said was believed. The cruelties the poor folk were subjected

to when supposed to be possessed by an evil spirit were terrible;

we have known of several patients who died through the cruel

usage of these medicine men and their wives.

For three years they did all they could to hinder our work,

and would not allow their children to enter our Homes.

I once asked an old witch doctor to let me see one of the

spirits he had taken out of a man's back. He said he could not

possibly show it to me, but perhaps some day he would let my

husband see one, and I told him that would do just as well. Long

after this he came to the door all painted and in a very excitable

state asking, "Where is our Friend?" (the people so

spoke of my husband). I told him he was in the stove. The witch

doctor had both his hands closed, and said he had a spirit, but

he was afraid it would disappear or change into something else

when my husband looked at it. I bid him make haste, and off he

ran, and when he opened his hands there was only a piece of mussel

shell. "There!" said the old man, "I knew that

it would turn into something else if we let any but our own people

see it."

Some of these men were very cruel, and did not like us in

their country because their trade [23/24] suffered as the people

became more enlightened. We noticed that however scarce food

was these medicine men always had to be thought of. For a long

time the people would not go into certain woods because of the

evil spirits. Sometimes a child's nose would bleed, very much"

for the child's benefit, but these men would tell its friends

that some one--naming a person miles away--had ill-wished the

child. Then an oration would begin. I am thankful to say there

are very few of these men left now.

Bread shall be given. Once the people were very badly off

for food, and being ourselves short of provisions, we greatly

feared that we should have to send the children out of the Home.

Before doing this we held a Prayer Meeting, and asked God to

send us food, if it were His will. We had been expecting the

Allen Gardiner for a long time. Next morning we heard

a great shout, and thought it was the Allen Gardiner;

but God had answered our prayers by sending a large whale, which

was stranded on an island near. We were most thankful, for this

provided the people with food, and we were able to keep the children

in the home. The medicine men said they knew a whale was coming,

because: there were signs in the rainbow that told them.

Several of the women in their kindness came, and said, "God

has answered our prayers, and has-sent us food, but none has

come for you; you cannot eat whale." Nor indeed could we;

we had seen it eaten by the hungry people in such a putrid state,

[24/25] that I felt I could not eat any to save my life. So they

said, "Do you think you could eat some larper?" This

is like a large mussel, and the shell was used by the people

as a tool in the early days. They got up at two in the morning

to work a certain tide, and brought us in a number. Our food

from England came a few days after.

A Visit from our Bishop.

We were always much refreshed and cheered by the visits of

our dear Bishop Stirling. When he first came to our station he

was struck with the look of hunger on some of the people's faces,

and said he should like to give the people a good meal before

he left.

We began to prepare at once. I made a large quantity of bread,

so did the cook on board the Allen Gardiner. That alone

would have been a [25/26] grand treat for these poor savages,

as they then were; but through the Bishop's kindness they had

jam with the bread, boiled rice with sugar and currants, good

tea with condensed milk, and other things. My dear husband superintended

all the cooking, which had to be done in the open air in large

boilers.

We had not yet been long in the place, and many of the people

had never seen currants. Looking at the rice cooking in the boiler,

they asked what were those black things in it, and my husband

said they were fruit, and nice and sweet. But they would not

taste, believing them to be flies, and asked my husband to taste

first. So he did, then they ventured, and were delighted: "Very

fine. Very sweet. I like some more. Very good man Bishop."

The Feast.

The feasting was to begin at 5, and I was looking at all the

loaves to be cut up, and wondering how I should be able to do

it all. My poor husband had enough else to do, and in fun I asked

him however I was to cut up all this bread. He had occasion to

go to the schooner to see the Bishop, who promised not to come

on shore that day till 5 p.m., and on the Bishop asking how Mrs.

Burleigh was getting on, my naughty husband said, "I have

just left her wondering how all the bread was to be cut up."

Presently the Bishop and Mr. Aspinall, who had arrived from Ushuaia,

came on shore, and the Bishop asked me for one of my big aprons.

Then he and Mr. Aspinall cut up all the bread, and put the jam

on.

[27] The people thoroughly enjoyed their treat; the only wonder

was how they could eat as they did, We had not nearly enough

plates; some had tins, others brown paper, and for spoons mussel

shells, We all did our best to make them happy, and it was not

surprising that the day after the Bishop had gone they all came

and said, "Very good man Bishop. We plenty like Bishop come

again."

The First Convert.

Our first convert was a medicine man; one of the oldest men

there, and one of the most degraded. I well remember our first

Sabbath after our arrival amongst these dear people. We were

holding morning service under a tree, and there were a large

number of natives assembled. My husband was speaking to them

from the words, "Behold, I bring you glad tidings,"

and all were attentively listening. Presently in the distance

we saw a very strange sight. Having only just come to the island,

we had not yet seen a medicine man dressed up as when they visit

the sick. He was painted, and looked a ghastly object. Having

noticed a crowd of people, he made for the spot, and was very

excited. Presently he came up to us, and stood and listened very

intently; I thought he had come to fight, he looked so savage

and angry.

After the service was over he pushed through the crowd and

came up to my husband and said, "I have been listening to

what you have been saying, and I never heard anything like that

down [27/28] here before. You have been telling us of a man whom

you call Jesus. He seems to be a very kind sort of man; we should

like to see Him very much. Is He coming here to see us?"

Then he looked at my husband and asked, "Who are you?"

He replied that he was his friend, that he was very glad to see

him, and who was he? Thereupon he introduced himself as a medicine

man of the country. We both offered a prayer that this dear old

man might find his Saviour.

We went home with him to his hovel, and I stayed as long as

I could, I felt so interested. This was the first token that

God was with us. My husband was with him for nearly two hours,

and when he rose to go, the old man said, "Do not go yet

I want to hear more of this good news. He could hardly believe

that there was someone who really loved him; he kept on saying,

"Only to think that there is some one who loves us? He found

Christ, and became a true and happy. Christian He was always

a regular attendant at the daily morning and evening prayers

I saying, that when he heard the bell ring he felt he must go

He told us his history, and from him we learned a great deal

that was afterwards most helpful to us.

About three months after this he caught a severe cold; bronchitis

set in, and being a very old man we were anxious about him. One

day when the bell was ringing for service I saw him coming, and

knowing that he was too ill to be out I went up and told him

that he ought not to have come this morning. He held up his hand

and said, "Do [28/29] not send me away. I shall die soon,

and I want to hear all I can." That was the last service

that he was permitted to attend.

It was a great privilege to be with this dear old Christian.

He would often say, "Call in some of my people"; and

when they were in, he would beg them to leave off their sinful

ways, and to listen to the good news that their friends had brought.

"Always be kind to them," said he, "and help them,

because they are the first white people that have brought us

such good news." He would pray so simply, asking God to

forgive their past wicked lives, the presence of his my desire

is to be my friend, will you baptised and to be very sweetly

of his

One day he asked my husband when it was that he first heard

the good news, and on being told that it was when he was very

small, and that his mother had taught him, the poor old man said,

"Ah, my mother never knew, never knew. Why did you not come

before? Why did you wait all this long time, and now only one

man has come? You have told me about your country and the good

people there are in it; you go home and write to your country

people, and ask more of them to come, so that all our people

may hear this wonderful news." Another day he turned to

me and asked if I would take his daughter and let her live with

me, saying, "Teach her what you have taught me because I

want to meet my child in Heaven." I did take her, and she

was a very good girl, and most helpful in the Home.

The First Christian Burial.

A little while before he died he asked my [29/30] husband

what they did with the dead in our country, and on being told

he said in the presence of friends, "When I am dead, my

desire is to be buried as a Christian; and, my friend, bury me?"

He asked to be called Samuel, and he spoke very sweetly of his

readiness to depart to be with Jesus. We did not think his friends

would carry out his wish, because the rule with them in their

savage state is to burn down the house, make most hideous noises

to drive away all the spirits, and run away with the body. But

seven of his relations came and said, "It was this man's

wish that you should bury him. We leave the body with you;"

and they all walked out of the wigwam. Accordingly he was buried

as he had wished, and this was our first Christian burial at

Wollaston.

How cheered we felt, and how we thanked God! It was indeed

worth all we had gone through, and much more, if only this one

soul had been saved.

Amongst the Children.

Amongst the children it was most happy work. When we found

what sad lives some of these dear ones were living we determined

to care for them. Many of the parents were very indifferent.

At first we could only put up a wigwam, close to our hut, and

the next morning fifteen came to be taken in. How our hearts

went out towards them! They were in a most wretchedly filthy

condition; I had no clothes for them, and could only afford then

to give them one meal a day. However we could [30/32] give them

a good fire, and when the storms allowed I took them on the beach

to gather shell fish.

My first efforts were to get them clean. They used to laugh

and say, "Very funny woman you. I think English woman plenty

like wash." I was very proud of my new family when at last

I did get them clean, and learnt to love them very much. They

used to run after me wherever I went, and say such funny things:

everything was so wonderful to them. It saddened us very much

to see them always looking down. This was partly to be accounted

for by their always looking and hunting for food. Some of them

had sweet little faces, and were most lovable creatures.

They Learn Games.

I taught them some English games, and soon found that they

could enjoy them just as much as English children. "Here

we go round the mulberry bush" they were especially fond

of. We were all very happy together, and I often felt almost

a child again. In the early days, the mothers used to carry their

babies strapped on their backs, and as these children had no

dolls, they used to get puppies, strap them on their backs, and

strut about with them. The poor puppies were very thankful when

some dolls came, and they themselves were no longer wanted.

Visitors at 5 a. m.

On one occasion, when we were at Tekenika, about eighty natives

from New Year's Sound came to visit us. They had heard that there

was a little [32/33] white baby at the Mission station, and they

were very anxious to see it, and us also. At about five o'clock

one morning I opened the door, and there were all these people

outside. Some of them said, "We should very much like to

see the little white baby." It was very early, but I thought

it so kind of them, that I had better just let them see the top

of his head; so I brought him out wrapped in a shawl, for it

was very cold, telling them they must be satisfied to see only

so much, as it was very early, and he was asleep.

I shall never forget how they crowded round, saying, "What

beautiful white hair! He is our friend baby "; and then

the poor things looked at me and said, "We are very glad

to have you here, and you will be our friends." I told them

how very glad I was to see them, and to be in their country with

them, and that we were indeed their friends. I noticed three

of the men, who were painted nearly all over, disappeared behind

two large trees, and seemed to be doing something to their faces.

Presently they returned, having been trying to rub off the paint

with moss. I can only suppose that seeing I had a clean face,

they thought they must not come up to me till they too had cleaned

their faces. It may be imagined what their faces looked like

now all bedaubed with paint and moss. They went off to the store

to see my husband, who welcomed them, and asked them all to come

to morning prayers, which they all did. They stayed with us about

ten days, and when they went off, they wished to leave several

of their children with us. These were in a most pitiable condition,

[34] The Traders and their Evil Deeds.

[These were the men who came in search of the gold that is

to be found about these coasts.]

On another occasion about sixty visited us from another part.

They were fleeing from the cruel traders, and came to us for

protection. All those miles they had carried a poor woman in

a dying state. When they got to our station they laid her down,

and the medicine men began performing their cruel rites on her.

Some of my women happened to be near, and she looked up and asked,

"Where does our friend live?" The house on the hill

was pointed out to her, and she said, "I have heard of her,

and want you to take my two children to her, and ask her to take

care of them for me; for I am dying, and cannot go to her myself.

Tell her that their father was shot by the traders." The

woman brought me the two miserable little objects; they were

very frightened when they saw me, and I asked the woman to stay

in the hut while I ran down to promise the poor mother that I

would care for them, but when I reached her she had just passed

away.

I felt that these two orphans were a sacred charge, and I

did try to care for them. The first thing was to get them clean.

I gave them into the charge of two of my best girls, who I knew

would be kind to them. They grew up to be very good children.

Since we have been in England my daughter, with the help of friends,

has tried to collect enough to support the girl, and has done

this until God saw [34/35] fit to take the child home, and now

the same friends are helping to support the boy.

There was a man in whom we were greatly interested; we hoped

that he was really trying to live a good life. Some of these

traders told him that if he would give them his skins they would

give him something that would keep him warm and make him merry.

He yielded to the temptation--as alas so many did, for these

poor creatures had not the strength of character that we might

have--and some days after he was missing from his work. He was

found lying dead on the road, with a bottle of this poisonous

drink in his pocket,

A poor old savage who lived about ten miles away by water

used periodically to visit our mission. We did not encourage

the people to settle with us, for we could not afford to give

work to them all. He had a very nice wife and a dear little girl,

and we were much interested in this family. We noticed that this

man had not been to see us for some time. My husband became uneasy,

and went to find out about him. As the boat drew near where the

man's wigwam was, the men thought they heard groans. My husband

ran up, and found the old man lying almost in the fire, and in

a pool of blood. Some miners had been there, and had stolen his

wife and daughter, and when the old man resisted they struck

him on the bead with an axe.

He was brought home to us, and partly recovered, but remained

almost imbecile. He was able to understand just a little, and

some while afterwards, when the poor old fellow heard of the

death of my dear husband, he came over at once, and [35/36] would

run round and round our hut many times in the day, howling and

calling to his friend to come out to him.

It always saddens me when I think of the times we had with

those wicked men. I am ashamed to say some of them were English.

Waifs and Strays.

Children would often come to our door and ask to be taken

in, and we never refused them. One poor little mite whom I had

not seen before, came early one morning; she had only a tiny

skin on her shoulders, a little spear in one hand, and a basket

on her arm. She began telling me that a number of people had

arrived in the night from another part, and then said that she

wanted to come and be my little girl. It was cold, and she came

in by the fire and told me a sad story. She had a very cruel

father, and though so young her life had already been a very

sad one. Of course I took her in, though at times I hardly knew

how to manage, our funds were so low. But God was good, and provided

for our wants.

My girls were very kind to her; they tried all they could

to get her clean, but found this difficult. One day I heard a

knock at my door; it was one of the girls who came to tell me,

"Please, mam, this little girl is very dirty. Flannel no

good. May I use the scrubbing-brush?" I looked shocked,

and asked, "When I took you in, who washed you?" She

said, "You, mam." I asked, "How long did I take

to get you clean?" "Long time, mam." "Did

I ever use a scrubbing-brush for you?" "No, mam."

[36/37] "Well then I cannot allow you to use one for her;

you must be patient as I had to be." Next morning she was

brought to me looking a perfect picture, and she grew up to be

such a nice child.

That evening I had taken her on my lap during evening prayers,

but when we began to sing she ran off and hid in a corner. About

three months after, I heard a sweet voice singing "There

is a happy land," and was told it was this girl.

Delivered from Fear of Death.

One girl we had in the Home, and who died there, always had

a fear of death. She was a good girl, and I used to talk to her

and try to comfort her. One morning the others came to me and

said, "Our friend now is not afraid to die; she wants to

die." It seemed that during the night she had seen the Saviour

in a dream, and, said she, "He smiled at me, and said, I

want you to come and live with Me. He bent over me, and took

my hand." When she awoke she was dreadfully disappointed

at its being only a dream. To the girls she said, "You must

try never to be naughty again. I am sure if you could only see

His lovely kind face you never would." And, she added, "Make

haste and send for me, Jesus, I do want to come," and that

same day she went home to Him.

The children were very fond of our good Bishop. He did like

to see them playing their games and being happy, and he especially

liked to hear them sing "I will arise." In Yahgan those

words are very sweet.

[39] In 1892, the Station was moved to Tekenika, on Hoste

Island, a much better position than on Wollaston Island, and

we were very pleased that the people were all so willing to go

thither. Here we still had our hut, but we also had a nice Home

for the girls instead of a wigwam or log hut as at Wollaston,

and we put up a temporary Home for boys, for the poor little

fellows wanted as much caring for as the girls. The boys have

now a substantial Home, built by Mr. Pringle; there is also the

Church and a house for the Missionary. On the whole we were greatly

cheered in our work at Tekenika.

Five Weddings.

After my great sorrow (of which I will speak later on), Mrs.

Hemmings very kindly came to take my place for a time, and she

felt the responsibility of having so many children to look after,

particularly the five elder girls. I was making this a subject

of much prayer, for these dear girls had been in the Home many

years.

Just at this time our good Bishop visited us, on his return

from Keppel. One day he said to me, "Mrs. Burleigh, there

is something I should Ike to speak to you about. I want you to

help me, and only you can do so in this case." He went on

to say that he had brought five good young men from Keppel Island;

they had heard of our Home at Tekenika, and wished to be allowed

to choose from it their wives. I recognised this as God's answer

to my prayers. [39/40] I told the Bishop of these five girls,

and it was arranged that on the Sunday afternoon the five young

men should come and see me.

I told the girls all about it, and that I should soon be leaving

them. The poor things asked the very natural question, "How

do we know we shall like them." I told them that on the

Sunday afternoon I should introduce these young men to them,

and after that they would have an opportunity of finding out

if they knew them or any of their relations; but before this

I should have a good talk to the men. I asked God to help me,

for this was quite a new experience.

On the Sunday afternoon I saw the young fellows coming up

the hill. Of course they were rather shy, and did not like to

come up to my door, so I went out to them and said, "I think

you are looking for me?" They replied, "Yes, mam,"

very politely, lifting their caps. I invited them in, had a long

talk with them, and was very pleased with their straightforward

answers and all they said, and having heard that Mr. Whaits at

Keppel was able to speak well of them, I really felt very thankful.

The Wooings.

After this I went to fetch out my five girls, very shy, poor

things, catching hold of my arms and dress, and when I got them

into the large day room they ran away into corners. But I hunted

them out and introduced them, and then said I should leave them

all to have a talk and to find [40/41] out about each other,

and they were to knock at my door when all was settled,

I went into my room and told the Bishop what I had done. He

was amused, and said, "Well, now we must listen for the

knock." I was busy here and there, and presently when I

came into the room the Bishop and Mrs. Hemmings said they thought

they had heard a knock. I opened the door, and said I supposed

they bad finished their talk, as they had knocked. One young

man got up and said, "No mam, we not knock. You come too

soon; only one man finish." I begged their pardon and quickly

retreated, but about half-an-hour after this there was a great

knock that could not be mistaken, I went in, and a most interesting

sight presented itself; by the side of each young man a girl

was seated, and all looked very happy.

To many this may appear rather a strange way of doing things,

but those who know the Fuegians and the many temptations awaiting

these young men in Tierra del Fuégo when they came from

Keppel, will say that it was the best thing that could have happened

to them all. I found that these young men and women had known

each other's relations, and that three of the girls had known

the men when they were small boys. When I had heard all, I thought

that the whole affair was admirably managed. I had told the eldest

girl that I should like them to have a cup of tea. Mrs. Hemmings

and Mr. Pringle joined us, and the Bishop asked them all to come

up in the evening and to bring their friends, as he wished to

speak [41/42] to them. We had a very enjoyable service together.

I have not mentioned my dear husband's name; he had been called

to the better world only six weeks before. Next day the Allen

Gardiner left for Ushuaia, taking the Bishop and Mrs. Hemmings,

but the Bishop hoped to return in five or six days, and then

the weddings were to take place.

The Trousseaux.

After the Allen Gardiner had gone, and we were all

quiet, I told the girls that very probably in five or six days

they would be married, and that as I had some material I should

like them to make their own dresses. I shall not easily forget

how those girls worked; they rose at 4 a.m. to get all the work

of the Home done, and by 11 they were able to begin their dressmaking

and outfit preparation. Our women and girls were accustomed to

make their own clothes. I cut out for them, and by the end of

the fourth day all was ready. During these days the young men

had been allowed by Mr. Pringle, who most kindly helped them,

to put up their dwellings.

The Ceremony and the Feast.

On the morning of the sixth day the Allen Gardiner

came in sight, and a busy day it was. The younger children went

into the woods to gather evergreens, and some of the elder ones

helped to decorate the room. As we had at that time no church,

the room had also to be used for service. The five girls were

intent on preparation [42/43] for the feast that was to follow

the ceremony. The Bishop had brought some fresh beef from Ushuaia,

there were preserved potatoes, plum puddings, and other delicacies.

The tables were covered with calico, the dishes garnished with

green, and altogether the room looked very pretty. What a contrast

to the first tea spoken of on page 26, when all the people were

utter savages. One part of the room was screened off for the

service. There were three long tables, one for the married couples

and their friends, one for the other guests, and one very long

one for the children belonging to the two Homes.

My dear husband had on a former occasion sent home for some

silver rings--we always gave the bride a silver ring--and I wondered

whether there were any left. On going to his desk I found on

a roll of paper just five rings, so that each girl had one. Mr.

Pringle very kindly made each one a box to put her things in,

and painted the name on the cover; of these they were very proud.

After the wedding ceremony came the feast. The Bishop presided

at the brides' table, the captain of the Allen Gardiner

at the next table, and Mr. Pringle, Mrs. Hemmings and myself

at the table of the children. The crew of the Allen Gardiner

were the waiters. Afterwards the Bishop spoke to the newly-married

couples, and the children sang hymns and two anthems, and so

the happy proceedings came to an end.

I was told after I had returned to England that some of these

girls and their husbands used to hold prayer meetings in their

houses.

[44] A Missionary Bishop.

Some might think that a Missionary or Colonial Bishop has

a comparatively easy time. Here is an experience to the contrary.

The Bishop and Mr. Pringle went one day in the Allen Gardiner

to look over the sheep island at some distance from the Station.

In the afternoon, as it was calm, they came back in the boat,

the captain intending to bring the schooner up later. By some

means or other she grounded on the beach. We did not know this,

and as the wind rose in the morning and was fair, we wondered

why she did not come. We could see her in the distance with the

glass, yet she remained stationary. This was between 9 and 10

p.m.

The Bishop suggested that she had got aground (which was the

case), and could not be got off till high tide in the early morning.

He then said to me, "Mrs. Burleigh, where can you put me?

If you will give me just a blanket I will lie down anywhere."

Our quarters were very small, and I hardly knew what to answer,

but I slipped out and asked Mr. Pringle how we had best manage.

He at once said I was to give the Bishop his bed, and he and

Mr. Lawrence's son would lie down in the store-room.

With this plan I went back as I thought triumphantly, and

told the Bishop he was to have Mr. Pringle's little room. But

with a stern look he asked where Mr. Pringle was going, and on

my saying that he was going to the store-room floor, he said,

(i who has been working hard to-day, Mr. [44/45] Pringle or I?

No, Mr. Pringle will have his own bed, and I will go to the store."

And he was quite determined about it, so I had to lead the way.

Sleeps on the Store-Room Floor. At that time only half the

roof was finished, and in that dry corner I had two little Fuégian

boys sleeping, for both the Homes were full, and two girls had

to sleep in the day room. The other part was cold, draughty,

and subject to rain droppings. This was where the Bishop had

to lie, wrapped in a blanket. I could not sleep for thinking

of it. About midnight I found that I had forgotten to bring in

baby's food, and I had to go to my cupboard in the passage, separated

by only a thin partition from the store, and it was a great relief

to me to learn that the Bishop really was asleep.

About 3 a.m. the captain was able to bring the schooner up.

Mercifully no rain fell that night. The Bishop knew at what time

the vessel would be likely to come, and I made sure that he would

be slipping out the back way so as not to give any trouble. I

took the key out of the back door, and between 5 and 6 a.m. we

heard the Bishop trying to effect his escape, but it was of no

use. I had been up for some time, and he had to give in and drink

a cup of tea before he was allowed to leave the premises.

My Great Sorrow.

I want to speak of the kindness of these dear people to me

in the time of my great sorrow. At [45/46] meetings I nave often

wished to speak of this, but have not felt able to do so. I dared

not trust myself.

In December, 1893, we had been much tried by the visits of

miners to our Station, and on this occasion 25 had come to us.

We were obliged to house all the women at night. The miners'

plea was that they came to look for gold; they sent a message

to us that they intended either to shoot us or to burn us out.

It was a very anxious time, but on former occasions our lives

had been so wonderfully preserved by our Heavenly Father that

we felt sure He would protect us now also. We were very thankful

to have Mr. Pringle with us as a helper.

All the time these miners were in the place the house was

guarded. On one occasion my husband and Mr. Pringle thought the

place was quiet, and being worn out for want of sleep, they came

in to try to get a little, but soon our faithful old dog gave

a growl. I let him out, and a man was found under the house trying

to set fire to the building. On hearing the dog he took to flight.

Next day several of the men came to the store and said, "What

a nice dog you have. We should so like to have it, and we will

give you anything you ask for it." When they found we would

not part with it, they tried to shoot it, but did not succeed.

On many occasions our lives have been saved, humanly speaking,

through the faithfulness of that dog.

Next day, Saturday, December 23rd, they left, after having

wearied us for nearly a fortnight. [46/47] How well I remember

that terrible day. It was my husband's custom on the Saturday

half-holiday to take the boys for a long walk, or if the weather

allowed he would take them in the boat. On this day he was worn

out for want of sleep, and I advised him to try to get a little

rest in the afternoon, and let the boys go alone. He did try,

but could not. As it was so near Christmas Day, and he always

made some toffy for the people at that season, he said that he

would prepare it, which he did, and I told him that I would finish

it, and let him again try to get some sleep.

He could not, but went off to meet the boys coming home, saying

that he would cross just a very little way in the boat to save

walking all round, and that he would bring them all back in the

boat. In the morning he had arranged with a man to go with him,

but the man had forgotten, and when my husband got down to the

boat he thought that he could manage it alone, as it was calm

and the distance very short. Mr. Pringle was busy in the store,

and knew nothing of what was happening.

The Fatal Gust.

When my husband was in the act of crossing, a gust of wind

came. He had the tiller in one hand and the sail-rope in the

other. Evidently he was not expecting this gust, for it took

the rope out of his hand; he made a grasp to get it, and fell

overboard. I was standing with my baby in my arms watching him,

and I saw it all. He had waved his hand to us the moment before.

The [47/49] people did all they possibly could to save his precious

life, but the tide was unusually high, all the canoes were moored,

and it took some time to unfasten them, and then it was too late.

Oh, the anguish of watching the empty boat slowly drifting on

to the beach.

When the people found that their friend was really gone, some

of them who were not Christians were about to resort to their

frightful savage customs as a mark of respect. When I saw this

I went up to them, and asked what they were going to do. They

said, "Why, wouldn't he like it?" "What,"

said I, "after all the teaching you have had?" Then

it all seemed to dawn upon them, and they were as quiet as children,

no howlings, no noise; all that could be heard was weeping in

their houses. I thank God for what I was enabled to do. I just

asked Him to keep me calm, and that I might retain my reason,

and indeed He was good to me. I turned to my Bible for comfort,

and the first words that met my eyes were, "I will see you

again, and your heart shall rejoice." I was as it were fed

each day with some of the most beautiful promises from God's

Word. I was able to go home and to attend to all the wants of

the children in the two Homes. I can never speak warmly enough

of Mr. Pringle's kindness to me and mine, nor of the good Bishop's

sympathy and support to me in my sore trouble.

The Sympathy of the Natives.

It was eight days before anyone could come to us. The dear

natives sent me a message to say [49/50] that they would not

trouble me at all, and would not come near the house, but would

I promise them one thing--that I would not stay in bed. They

feared that if I did I should die, and they asked that each morning

I would go to the door or wave to them from the window, and they

would know that I was not ill.

I did this for two days, but could no longer bear their staying

away; it seemed to comfort me to have them round me. I can never

forget the kindness of the children in the Homes. They rose early

and got all the work done, that they might come and sit with

me, and in their lovable little ways try to comfort me.

Can people wonder when I tell them how-dear all these were

to me? Since I have been in England I have travelled a great

deal, and addressed many meetings, and I have been asked, "How

could you live with such low degraded creatures? Did they not

try to hurt and kill you?" My answer has been, "It

was not the poor natives we had to fear, although in the early

days great tact was needed. Our danger arose from those who ought

to have known better, and who ought to have set the poor savages

a better example--from the traders and the miners." With

them we had sad experiences indeed. These are the men who bring

discredit on Christian work, and who taught our people to swear

and drink and fight.

My husband had been so looking forward to seeing Bishop Stirling,

and he had composed a hymn of welcome to be sung by all the children

on his [50/51] arrival. This hymn was sung on Christmas Day.

The people also had their toffy.

Twelve Quarts of Liniment.

About four days after the sad event I was waited on by a number

of the older people. They said, "We are afraid now that

we shall soon all die," On my asking why, they enquired

how much liniment I had left, and were told there was only a

very little. My husband used to make up this liniment, and found

it most useful and suitable for the people. As for them, they

had the greatest faith in it; if the poor old souls had only

a headache they would come to me for some liniment. Now they

thought they should die, as there would be no more to be had.

I told them that I had helped their friend to make the liniment,

and that I would make them some. They were greatly pleased, and

when they heard that I should soon be leaving, they begged me

to make them plenty of it before I went. The Bishop helped Mrs.

Hemmings and myself, and we were able to provide no less than

twelve quarts for use after my departure.

Conclusion.

Since I came home many have expressed their pity at my having

to live in such an out-of-the-way place and with such people.

I always tell them that we both were perfectly happy in our work.

Next to my great sorrow, and the loss of my mother, my greatest

trial has been to leave those dear people, and up to the present

God has [51/52] not shown me that it was His will that I should

return. The future I desire to leave entirely in His loving hands.

I have indeed had proof that He is a Father to the fatherless

and a Husband to the widow. For what little we may have been

enabled to do I desire to ascribe all the praise and glory to

His Holy Name.

To any into whose hands this little book may fall, and who

may be called to work among the heathen, I would say that it

is a most happy and glorious work, that it is a high privilege

to be allowed to be the humble means of doing ever so little

for Him Who has done so much for us. The seed sown does bear

fruit, and little cheerings often come to the worker to show

that the work is not in vain.

The fields in South America are white unto the harvest. This

little corner that I have been speaking of is but as a grain

of sand on the seashore compared with the vast regions of that

continent. May God put it into the hearts of many to come forth,

not only to give of their substance, but also to say, "Here

am I; send me."